I wrote the first few sentences of this piece two or three years ago; the rest was completed on a whim during a two week cruise (which, for the record, I’m still on). Way back when I started the intro, I called it my “bad Pynchon imitation.” Now, after a few days of cycling through “Zadie imitation,” “Roth imitation,” and “DFW imitation,” I figure I’ve imitated enough disparate authors to just call it “done.” Self-deprecation aside, I’ve never attempted a piece of fiction this long before; I tend to be much more comfortable in dense, quippy, 4-5 minute bursts. But this story has nagged at me for quite some time, and to be honest, I’m quite proud of the result. I hope you enjoy reading as much as I’ve enjoyed writing!

I’ve copied the story in plain text below. If you hate reading lengthy web pages as much as I do, you can also grab the PDF here instead. This is a fictional story, though it is inspired by a number of real places, people, and situations. (And, of course, that song.)

Angels in the Architecture

These are the days of miracle and wonder

And don’t cry, baby, don’t cry

— Paul Simon

*

Light fills the room that is all window, blinding, but it isn’t a metaphor for clarity. It’s just the sunrise wriggling through a yellowgray fog, 30 stories high above the Yangtze River, illuminating statues and schooners and surgical-masked joggers before striking the corner suite at its eponymous point. It nudges him awake as it sweeps the floor diagonal, flooding his spirit with a feeling he’d purchased. The room is ostentatious and virtually empty, housing a sky-blue suitcase under a crumpled up coat, upside-down shoes and a (hopefully) passport; but there’s nothing signified by all that negative space, calendar notwithstanding. A king-size bed with half the pillows kicked off, laptop resting where a head’s supposed to be, is no more poetic than it was on the 13th. And there’s nothing profound about the skyline jutting from the opposite bank, its sharp angles smoothed sinusoidal by haze; neither the fact of its bigness nor the admission that he’d, truthfully, expected bigger.

Daniel’s head is throbbing and his still-on bluejeans smell the way his throat tastes: blood salt and woodchips. He pieces together what he can as it comes. He remembers a cowboy hat hawking ill-advised shots; a woman whose Nikon hung from a strap. Untranslated monuments. Hours packed in an establishment so tiny it could tile the present suite four times over. A prelude, first, of beef stew and Tsingtao, under a canopy the color of old headlights: a thick, smudgy clear that looks melted. Tentative smalltalk, forced laughs on cue. Saying yes to questions he didn’t actually hear. Waxing bullshit philosophy while pretending to inhale, all unwritten contracts of the Male Heart-to-Heart. Eventually forgetting to pretend—hence, woodchips. Stumbling back to the hotel, heart racing, alive with something he’d insisted was more than romanticized nonsense. Head spinning with future conversations about said epiphany; head barreling into the polished, triple-paned glass of the Marco Polo Wuhan; head landing just short of the open lobby door.

None of this matters, and he’s resisting the urge to let it. It always happens this way when traveling alone: Everything gets amplified, distorted by a put-upon significance no sober morning can withstand. The sunrise, the hangover, the piecing-together of such and such lost evening. It’s exactly the type of banal story that, back home, would have him scrambling for an excuse to leave the conversation. You drank with a stranger and walked home, poorly, but because you’re in China it’s suddenly meaningful? One hemisphere’s pathetic is another’s spiritual, he supposes; a sort of currency exchange for fleeting sensations. It’s shallow. It’s appropriating. It’s exactly what he paid for. And yet: Granting no metaphor to light or poetry to bedsize or profundity to an upsold Travelocity skyline—aware that loneliness diffuses details into splotchy abstractions, like so much canopy or yellowgray fog—with each hamfisted symbol put firmly in its place, there still remains the issue of that voice. How it sounded, unexpected. How it broke him, in earnest. That moment when a bearded mouth undrawled itself and angels issued forth, that doesn’t get to be nothing like all of the others. It shattered some context, some triple-paned certainty. It couldn’t be willed back in place.

**

There are some things he feels and some things he knows, and they’re often in stark competition. For instance: Some small part of him feels he can tell when he’s about to get a phone call. Even when the ringer’s off (which, Daniel being a chronic people-pleaser whose tendency towards unobtrusiveness borders on obsessive, it always, always is). As if the inbound transmission literally rippled through the fabric of his left front pocket, like some cellular tingle or digital itch. Taken at face value it’s ludicrous, and hand-wavey explanations about “electromagnetic waves” only make it worse—mile markers on a highway to tin foil and crystals. He knows it would never bear out in a double blind study, that it’s a textbook example of confirmation bias at play. But when he’s staring down the barrel of a silent Incoming Call, a textbook’s not always top of mind.

He feels she can save him and he knows that she won’t. About his age, 30 or 35, too old to be here on a post-college backpacking trip but too visibly undead to be here for work. Gun to his head, German, though he couldn’t be sure. She’s walking through the Esplanade just after sundown, wisps of blonde hair spilling out the hood of her puffy green vest. Expensive-looking DSLR swaying like a pendulum from her neck. Her pace is slow, given the now-fading light: plodding around various historical monuments, snapping pictures whenever something catches her eye. They’ve already done a full lap around the interesting bits of the park, and now it’s devolved into an awkward, Brownian dance—criss-crossing glances, feigned interest in plaques. Neither wanting to actually meet the other, neither quite ready to pack up and leave.

They’ll stay in that limbo all evening, he’s certain, and upon sober consideration it’s all for the best. Things rarely work out like a Linklater drama; in real life, you’d probably come off as a creep. A stranger in a park observes your neutral behavior, projects onto it layers of hidden intent (“wanting,” “feigned,” “dance”), and decides to start a conversation—what would you call it, Sherlock? Still he finds an irrational camaraderie in these wordless exchanges. Like she’s asking “No, you first: What are you doing here?”

In the ten days since he was rushed to Wuhan on business, he hadn’t seen a single foreigner until now: not on his flight, or the client’s HQ, or the luxury hotel in which he’s been dutifully stowed. Even at the tourist traps on his rare evenings off, not a soul brushing past him who wasn’t Chinese. And it shouldn’t matter—it doesn’t, he knows it. He has no more in common with this woman than anyone else in the park. But after ten days of silence, what you know starts to slip. You begin observing yourself in the passive third person, your life a collection of verbal clichés. “Alone in a crowd.” “A boat against the current.” “Not all those who wander are lost.” Fodder for a brooding Tumblr page. Mundane activities, like throwing on a coat and scrounging for dinner, take on a certain elevated, literary hue. A wrong turn at a stoplight becomes a meditative journey. A fumbled transaction at the cash register opens up some gaping ravine, between outside and inside, between you and the space you inhabit. Your fundamental loneliness becomes blown up, permanent. Like you’ve always been drifting, just like this evening. Like you aren’t 18 hours away from boarding a $4k flight home on some international corporation’s dime. Like you aren’t walking the exact route suggested to you, in impeccable English, by the hotel concierge while drawing an oval with a Sharpie on a foldable map.

No, tonight Daniel’s a martyr, a protagonist, a metonym; a spiritual nomad barreling through the unknowable dark. And he wants to think she’s sharing it, that pilgrimatic ache. To see her Nikon as a talisman that heals invisibility; her expression as a curled half-smile and not a vacant stare. To find in these awkward glances not the random intersection of two rotating rays, but an intentional, sacred communion. This is my body. This is my blood.

Except: textbooks. White bread and grape juice.

***

This trip, like most, has had a bleary quality to it. He was sitting in the office one afternoon when he got the same call he’d gotten too many times before: “The client is furious; how soon can you be here?” In the past, there would have been frantic arrangements, canceled dinner plans, apologetic I.O.U’s to factor in; not this time. He’d finally achieved what the armchair philosopher in him always dreamed of: He was completely, hyperbolically untethered. No one to ask for permission. Not a single reschedulable plan. Nothing to do but trudge home to an empty apartment, dump half a drawer into a beat-up blue roller bag, and hail a Lyft to the airport. Four hours all in, from phone call to boarding, and that was including two Old Fashioneds in the business class lounge, sipped with practiced cinematic intensity. And the requisite social media post to go with it, of course. What a crazy adventure. What a badge of worldly honor draped in translucent humility. See you all in two weeks! (As opposed to when, exactly?)

As he sits in the courtyard of some nondescript eatery, he can’t help but feel that the romance has waned. After a decade or so of jet-setting, that adolescent thrill is still (shockingly) present, but its half-life has grown notably shorter. The same excitement that once propelled him through weeks of post-travel slideshows and re-rehearsed stories, now struggles to survive the length of a flight. Reality always had a way of setting in: the infuriating taxi stand, the sleep-deprived lunch meeting, the fluorescent conference room with its halfassed motivational posters (“Dedication,” “Foresight,” “Brillian [sic]”). Even the location-appropriate beer ordered just after touchdown, regardless of jet lag or hour of the day: It was all part and parcel of one weary routine. He used to go miles out of his way to find the perfect hole-in-the-wall, the Bourdain-sanctioned Authentic Experience about which he could wax poetic for months on end. Now he’s plopped down at the first spot with an English menu he could find, three blocks at most from the Sharpied Esplanade. Debating between two options, “Chicken” or “Beef,” based on two near-identical photographs. Nursing an unwanted Tsingtao (see: weary routine).

Another element that belies the Instagram narrative: his perennial headphones. Through every one of these brooding walks, dim-lit flights, solo dinners—even that imagined interaction with the puffy green vest—he was listening to something. Music, occasionally, but more often podcasts: Ira Glass, celebrity interviews, political debates dialed to chipmunk speed. Always hovering somewhere half-between comprehending and not; parsing the words’ rhythm and cadence but rarely absorbing their content. It’s a strange habit for a self-fashioned “spiritual nomad,” this near-religious rejection of silence. But to him, on this trip, it doesn’t subtract from the illusion so much as underline it. That lush inner ecosystem of film reviews and field reports, jut up against the vast, inaccessible Out There.

Safely at rest in his assumed final stop, and cushioned by voices chirping yesterday’s news, he takes stock of his surroundings. The metal table with its thick film of dust. The laminated menu card with red and yellow stripes. Only three other patrons, here for booze and cigars—not a great omen for the food. The sun he’d long since perceived to be fading is still holding strong; or weakly, at any rate, clung to a perma-gray twilight. Green plastic chopsticks in a green plastic cup. Foot traffic now pared down to a trickle. The waiter/cashier/owner smiling from a respectful remove, an if-you-need-me-I’m-here-but-if-you-don’t-that’s-fine-too. Everything in its proper place, unhurried and fine. The courtyard is shielded by a clear, plastic tarp, though it doesn’t look like it will rain. His neighbors have taken out playing cards. “Michael Flynn has resigned today as National Security Advisor, following controversy over his alleged contact with Russian…” The tarp is splotched with an iodine yellow. The cup isn’t the same shade of green as the chopsticks. From here it’s a straight shot back to the hotel; he should be in bed by 10 at the latest. Do they have different card games in China? He should know that. Even the beer bottle looks dusty.

He wipes the rim with a napkin, nods his head upwards in the direction of the waiter, and removes a single earbud.

****

Here’s the frustrating thing about pivotal moments: There’s no way to discern when you’re in the middle of one. Take the Flynn bit, for example. At this point it’s just one of a thousand details the chipmunks have run through. Trivia for the diehard NPR fan. Daniel has no inkling that a year or two later, this flash-in-a-pan advisor will have become a near-household name. Nor does he imagine the aforementioned “Russians” will tie in to a story so scrutinized, so loudly debated, that it will seem hackneyed and overwritten to even bring up; some Forrest Gumpian demarcation of era akin to the Watergate break-in or Challenger launch. That this story will evolve, like all things, from curiosity to scandal to nail-biting drama, before reverting back to soundbite and calloused retort. Tonight it’s just a tossed-off fact among many, no more remarkable than the Tsingtao he’s idly sipping or the holiday he’s pretending not to remember or the subpar stew he’s letting get chilly as the gray “perma-” twilight announces its end.

Daniel has no sense his certainties are about to split open. If anything, he’s ashamed of how obvious his journey has been. Ten days in a new city and nothing to show for it but three blurry selfies and a burgeoning cough. Years ago this trip would have been a goddamned story, or at least a goldmine of photo ops. Now it’s the third of its kind in as many months, and it’s barely warranted a footnote. Daniel still doesn’t know a thing about Wuhan, beyond the floorplan of various office buildings and the cocktail menu at the Marco Polo. In truth, his thoughts have never really left New York. He’s no longer resentful (that subsided in January), but he isn’t particularly excitable either. What he is, is stuck. Calcified. Certain of the predictability of places and things. He knows he’ll leave this lukewarm farewell dinner, walk home in silence (modulo headphones), have a few more beers delivered to his suite, bathe in a glass box surrounded by skyline, eventually remember why he doesn’t like baths, and swipe through headlines he’s powerless to change till he drunkenly dozes off. It’s the same story every time. It’s already been written.

Outwardly this evening will be presented as fresh and invigorating; yet another rung on the ladder to Progressive Citizen Of The World—a status which, like any mileage program, demands constant effort to maintain. There is always more to do, more to see to stay current. But the more of the world he sees, the less he’s able to differentiate from that which he’s already seen. His hotel this evening has already merged with others in Shanghai, in Shenzhen, in Hong Kong, in Singapore, Bangkok, Manila, Jakarta, Taipei. Different languages, sometimes, and different cuisines, usually, but always the same focus-group-approved whiff of world-weariness; the same all-expenses-paid, feel-it-deeply-or-your-money-back sense of toothless wanderlust. Same clichéd cocktails ordered at the dim lobby bar, same sultry-voiced lounge singer with her affected lilt. Every suit-and-tie warrior in the place feeling the same lonely hum for two or three measures, before settling out tabs on their black corporate credit cards and heading up to masturbate atop identical sheets.

The whole travel thing was a farce, and how could it not be? What could you honestly expect from any one place, devoid of human connection? Eat and drink, drink and eat. Walk through the city from Point A to Point B, modulate slightly on the return if you dare. Try the X, it’s a delicacy here. Remember to Y before tipping your glass. Look at this museum, this tower, this skyline. Ponder your relative smallness therein. Let this body of water instill a preternatural calm as you stroll along its banks with the metropolis to your right. Yangtze, Liffey, Danube, Seine, the Bund, the Bosphorus, the Circular Quay. All beautiful places, make no mistake, and if he walked by the water he could still feel that promised tranquility. He could just no longer unsee the machinery at play. It was all too easy, and easy was cheap. Tweak the script, rotate the scenery, and watch as the epiphanies start tumbling out.

*****

“Yes, you!” the Uzbek repeats as Daniel pulls out his AirPods. “My boss wants to invite you inside for a drink.”

He’s standing in front of a cramped little dive bar, just off the main thoroughfare leading back to the hotel. It’s the sort of place you might find in any major city in Asia: bar-seating only, some dozen patrons wide, space for maybe twice that to stand if they pack like sardines. Fronted by a cascade of sliding glass doors, with multicolored LEDs strewn from every conceivable anchor. Resting above the whole thing—and this, he admits, is new—is an illuminated sign running the full width of the venue, black stenciled lettering on mustard yellow: “HOT & CRAZY SUGAR DADDY.”1 And dangling above the entrance, scrawled onto a circular piece of cardboard: “Welcome to New York.”

He remembers the man as “the Uzbek” not because he’s some accent savant (in truth, he’s not sure he’s met anyone from Uzbekistan before), but because that’s how everyone in H.&.C.S.D refers to each other. Or at least, it’s how everyone is first introduced. The bartender’s from Hong Kong, the barback’s Turkmeni, and the Uzbek—well, it’s not clear what his job is, exactly, beyond corralling stray passersby in off the street. If they ever give out names, they certainly don’t repeat them. Except, that is, for the owner. His particular name will be repeated all night, so crucial it’s written in all caps out front: the titular Sugar Daddy.2

He was born in China, but that isn’t his home. His home, he specifies, is wherever he wishes: Texas, San Francisco, Spain, Australia, Brazil. You name it and Sugar Daddy has not only lived there, but fallen in love there and started a business. He explains this over their first (second?) shot of Jameson, though the precise nature of these businesses grows fuzzier by the glass. Textiles? Shoe repair? A thrift store chain? All might explain his peculiar getup: alligator boots, black leather pants, bright violet button-down and maroon leather jacket, Ozzy Osbourne sunglasses, gray cowboy hat. Pack of American Spirits protruding from his pocket, wispy mustache covering his full upper lip. At any rate, Daniel, friend, the past is the past. His new calling is to bring all this adventure—he motions grandly around the bar, twinkling, half empty, adorned with knick knacks and blown-up stills from 70’s auteur cinema—back home. To give locals a taste of a world they’ve never seen.

After five drinks and half a pack of cigarettes, it’s still not clear why Sugar Daddy summoned him inside. Not that Daniel would ever explicitly ask, of course. At this point, he assumes it’s part of an elaborate hustle—the implied-to-be-free shots, the manufactured familiarity of “Daniel, friend.” Peeling open lonely American wallets one tall tale at a time. And, in truth, he doesn’t really care what this night will run him. The cab is prepaid, breakfast will be charged to the room, and it’s not like he was about to exchange his remaining Yuan anyway. Better to throw a little currency at a Hunter S. Thompson-lite fever dream than live to see it quarantined in some bloated Ziplock bag, high above the coat hangers, scattered among the Euros and Rupees and Yen, stockpiled for a “next time” he’ll inevitably forget to make good on. At least this way he gets a bona-fide story from the deal. A liquor-soaked evening with a larger-than-life stranger, scam or no, is still the most photogenic thing to have happened on this trip. Crank up the contrast on those LEDs in the mirror, let them refract around the focal point of a half-empty glass, slap on a filter and watch the night glisten.

******

Note the arm’s-length remove of it all: the assumption of bad faith, the choice to play along, the cynical posturing for a future viewing public. If you talked to Daniel in person, you’d never dream he saw it this way. Watch his eyes widen as he recounts to his new “friend” the details of his journey, with meteorological grandeur: “It’s been a whirlwind trip,” “a flurry of activity,” “the storm has passed and I’m finally settling in.” As if he were truly feeling things with a first-person passion. As if it weren’t precisely tuned to elicit an emotional response; a response which itself he has already heard and grown bored of. As if it weren’t all one symphony of pulleys and weights.

Which isn’t to imply that he’s acting as he confides in Sugar Daddy (though the long pause-and-sips feel a bit overblown.) Like the river and tranquility or those pre-takeoff jitters, he truly does feel lucky to be here. He’s proud to have fashioned this life for himself; proud to live a night worthy of editing in post. It’d be cynical if he were merely going through the motions, but what if the motions reflect who he earnestly wishes to be? Dress for the job you want, “Dedication” and so on. It isn’t his fault he’s become a cliché. It isn’t his fault he sees every twist coming.

It sounds pat to say that things weren’t always this way, but it’s true. There was a time, not that long ago, when this moment would have sparked in him some fundamental aliveness, a blinding aura of romantic possibility wholly immune to self critique. Shimmering skylines, chance encounters. Perched atop the Marina Bay Sands, arms out in supplication to the world and its wonders, whispering to her without a hint of conscious irony: “I never thought I’d find myself somewhere like this.” Dragging that same sky-blue suitcase through a tropical rainstorm, ducking in and out of hotel lobbies, searching. The playlist he crafted in the cab to the airport, after finally accepting his mission had failed. The way it filled him with a sort of preemptive nostalgia, that neon-soaked soundtrack to what could have been. The conviction that heartbreak was somehow the most fitting end.

Three doomed relationships and untold playlists later, he still chases those emotional highs and storybook conclusions. But there’s a pattern to it, a formula, that he knows he can’t escape. The bar decor fits it. Sugar Daddy too. Even if the specifics couldn’t have been called in advance, he knows on some level that he’s been here before. It’s the Londoner at the rooftop bar studying hotel management, asking if he’d join her for a drink. The veteran journalist stationed in Berlin with extremely strong opinions about Benghazi. The trio of Aussies huddled in an Istanbul tavern, swapping stories so raucous they’d eventually be chased out by a red-faced owner (and Daniel, too, by association, almost forgetting his passport in the process). The boisterous Southerner who now stumbles in behind him, he too is cut from the same cloth. “Unpredictable character” has become just another archetype to him, catalyzing a mood he’s already penciled in. He and Sugar Daddy will banter until the conversation grows hoarse, debating politics and communism and the fundamental similarity of disparate things, and oh it will feel so wild and rejuvenating. Hot & Crazy, exactly as advertised! In truth, though, neither will leave any better than they came. It’s the same exact bar in every corner of the world. And that doesn’t make it pointless, per se. He’s not sure what it makes it.

*******

It’s been a few minutes since Sugar Daddy ducked out on business and the Southerner heaved down on the newly vacant seat. Even under that special, inebriated stupor that tilts “insufferable” into “interesting,” Daniel knows he wants absolutely nothing to do with this man. He is, to put it uncharitably, the stereotype of Ugly American purely distilled: overlarge camo jacket over a t-shirt with words, scraggly beard matted down the length of his neck, sweat pooling over a visible beer belly which jiggles as he yells (which he frequently does). Already drunk off his ass by the looks of it, coughing up smoke and dense wads of phlegm, slurring in a thick drawl even he must know the bartender can’t understand. At the moment, what he’s slurring is a torrent of folksy misogyny regarding the bar’s drink selection:

“Honey, beautiful, you must’ve misheard me. If I wanted piss water, I would’ve asked for piss water. What I asked was, was if you had any whiskey in this establishment. I’m not talking Crown Royal, Johnny Walker, that cat urine bullshit some traveling ad man sold you fifty years ago. I’m talking single malt scotch. Fine Kentucky bourbon. The sort of stuff that burns a hole through your esophagus and on down to your soul. A rye—you know that word, sugar pie? Bulleit, I bet even you’ve got that somewhere on the shelf. Say fella, you don’t exactly look Chinese if you catch my drift. You in for a shot of straight Bulleit rye?”

At this point, our protagonist could point out that this order is at least as obvious as any piss water exemplar the Southerner just rattled off. He could mention, pointedly, that he and Sugar Daddy have been dipping into top shelf liquor all night, that there was no shortage of “good stuff” to try if you had the mental fortitude to shut up for the love of God and act like a decent fucking human for once in your miserable life. He could close out his tab and end the trip on a high note, confident the evening would have only gone downhill. He could do all of those things, and probably would if he were sober or had even the faint outline of a spine (see: unobtrusive). Instead he says “sure,” lifts two fingers to the bartender, and accepts the cigarette being dutifully proffered him.

Thirty minutes, maybe an hour goes by in that spot, and you’d be hard pressed to call what they had a “conversation.” Unlike everyone else he’s encountered tonight, the Southerner has absolutely no desire to talk about where he came from. He doesn’t seem interested in communicating anything, really, though he expends an awful lot of words in the process.

“Thing you gotta know about this place” he spits, pointing at China, Bulleit spilling on his shirtsleeve with his gesture’s wide arc, “is there’re a fuck ton of people. None of that please and thank you horseshit you do back home. You want their attention, you gotta shout.”

“I can hear that, thank you. You’ve been here long, then?”

“Don’t matter! I’ve been here since I’ve been here, same as anybody else.”

“Great. And what brings you to this particular bar?”

“International man of mystery. Wanted a drink.”

“Here on business, then? Visiting the university?”

“A man’s business is a man’s business, and that’s the best lesson I can,” hiccup, “give ya, mister bargain bin peacoat.”

And on and on and on and on, until at last Sugar Daddy appears and grinds the blabbering to a halt. He looms there between them for a few seconds, wordless. Then the Southerner (who, Daniel presumes, given the relative quality of his outer monologue, possesses an inner one of such unimaginable hellishness that to be left alone with it for even a moment must feel to him an interminable torment; that he must, if for no other reason than to distract from the weeping of objectifying, liquor-glazed eyes and the gnashing of coffee-stained teeth, open his mouth and unburden) breaks the silence.

“Say there cowboy, you look like the kinda freaky motherfucker who could use himself a drink. Hope you like piss water, that’s mostly all they got. Sweetie, over here now, hey honey butt, what’re you deaf? One more—no, three more’a’the, the, this one right here. Pronto! Arrive-fuckin-dirche, or did I stutter?”

For the first time all night, Sugar Daddy has abandoned his sunglasses and cordial smile. He’s visibly livid, and Daniel thinks he understands. If there’s one thing a man with his pseudo-Bohemian inclinations can’t tolerate, it’s seeing his passion project—his labor of love—cheapened by this American, customer-is-always-right brand of entitlement. “Please leave my establishment,” he growls through gritted teeth.

“Well excuse me, your highness. And what exactly am I being charged with, then? Can’t a fella buy some liquid clever in a shithole like this?”

“I said,” his volume rising, “please leave my establishment. You’re a rude, drunken bastard, and you aren’t welcome any longer. Please settle your bill and leave.”

At this point there are twenty or so patrons crammed in the place, chattering, and it’s doubtful any but Daniel have noticed this exchange. But watching them face off, The Beerbelly and the Sugar Daddy, he can almost hear the cartoon record scratch—sees in split-screen that moment in a Western when the Sheriff steps into the saloon and invites the outlaw to meet him outside. (The cowboy hat might have something to do with it.) He thinks he can feel the whole room clenching, as merriment melts into violence. Feels himself implicated too, in a sense, suddenly caught in a third person plural: two drooling Americans seated shoulder to shoulder, bulldozing the Hot & Crazy’s every peculiarity as they swig from identical drinks. It’s the flipside, now, of “alone in a crowd.” He’s half of “two peas in a pod”: the recipient of a perceived communion, no more intended than the German in the park. He wishes he could spit it out, revert back to nomad. Wishes he could leave the evening in the same state he came.

The Southerner rises with unlikely bravura, his sweaty beard level with the pinch of the hat. He removes it from Sugar Daddy’s head with one hand and clutches him by shoulder with the other. “You know, we’ve got a saying about situations like this…”

********

It’s nearly impossible, in hindsight, to describe what is so life-changing about the incident we’re approaching. On paper it probably looks vapid, ethnocentric, trite. Like yet another bit of travel-tinted quirkery Daniel would doubtless embellish before hitting “Post”—the crowd suddenly expanded to three or so dozen, the meaty hand on leather shoulder pad sharpened to a menacing clutch. Everything meticulously choreographed, composed; the contrast slider pulled all the way to the right, until the gap between After and Before appears wider than possible, more stark than the truth of the story allows.

Because none of this should be particularly surprising, even with embellishment. Within those four walls alone, Daniel had already heard Cantonese, Russian, even Turkish (not that he’d recognize it; the barback had told him) spoken amid the din. And that’s to say nothing of the perfect English with which nearly every soul had greeted him on this “nomadic” escape; from the concierge to the tour guide to the waiter to the Uzbek to the gator-booted Daddy under the Southerner’s paw. Is it really so outlandish that the tables might turn? Is Daniel’s own Americanness so Platonic, so impenetrable, that the mere hint of reciprocity—the possibility that a Chinese man with a Texan accent and cowboy hat might find his dual in a neck-bearded Alabaman who speaks fluent Mandarin—seems totally unfathomable? Seems about as likely as the man sprouting halo and wings?

Former military. Operations manager for a microchip plant. Expat college dropout “teaching English” to pay rent. Mildly successful video game developer whose lazy objectification of East Asian women, combined with the flexibility of his job, has brought him to this university town, studying the language by day and terrorizing bartenders by night. There are a thousand possible histories that could explain the Southerner’s next few words—a thunderous punchline in sing-song Mandarin, whose meaning remains undeciphered—but when it finally happens, Daniel won’t be considering them. To him this will be a Pentecostal revelation, a movement of the Spirit, a tongue of holy fire set upon each and every head. When the Southerner opens his mouth and the room splits wide open; when the patrons of Hot & Crazy Sugar Daddy burst into laughter as if in on the same cosmic joke; when the Quintessentially Ugly American proceeds to buy every last one of them a round of top shelf bourbon, here is what Daniel will be thinking:

I am far from finished. I am not played out. My solitude is not hackneyed, my conclusions not inevitable. I am here in this bar, bearing witness to miracles, stammering and gobsmacked and awestruck and alive, surrounded by the sound of new things unfurling. I am 31 years old and my life is not over, my reserves of revelation nowhere near close to tapped. On any city block in any country in the world there is a dive bar like this one, just like this, with Christmas lights and stairwells or sliding glass doors hiding secrets no caption could capture or eye-roll subvert. I don’t need to chase her. I won’t will it back. I will love and abandon and long for and ache, and it will be new every time because I’ll choose it to be. I am here in this dive bar at the end of the earth, and the past’s dour echo has no bearing here. The future is uncertain. It’s mine to explore, to refashion, reword, repackage, embellish, discard, put on pedestals, undercut, overstate. It’s mine to deem interesting or bland or banal. I am here, not alone, filled with incident meaning, and I never thought I’d find myself somewhere like this.

Amen. Hallelujah. Ganbei.

*********

So he does it, the Southerner. In an operatic timbre, octaves high above his register, relishing in the rising and falling of elongated vowels. He slices the air with the brim of the hat as he belts his heartfelt aria. The room grows smudgy, lights dim and refract, around their intimate slow-motion dance—the Southerner’s eyes now sharpened with clarity, Sugar Daddy’s grimace curled into a smile as he yields to the lead hand (no longer a clutch) and they waltz and waltz and waltz away what little certainty Daniel has left.

The crowd truly has grown silent this time, just for a beat but it feels like forever. Then a collective inhale, some scattered applause, and an eruption of ear-splitting laughter.

Hugs are exchanged. A tray of overfull shot glasses is passed around and a chorus of cheers reverberates through the bar. Background chatter resumes as if on cue—peas and carrots, peas and carrots. The Southerner and Sugar Daddy light their respective smokes and converse with the rugged familiarity of old war buddies. Sharing jabs and exclamations in rapid-fire Mandarin, settling in for a long night of—what, exactly, would it be? Small talk with a moderate acquaintance? Reminiscences with a dearly loved friend? Juvenile insults traded with a stranger just sloshed enough to mistake jackassery for wit? In truth, it hardly matters whether they’ve done this vaudeville act a thousand nights before or whether they’re genuinely meeting for the very first time. Their backs are turned to Daniel at this point, and it’s all just as well. He knows now, more than ever, that the story’s run its course.

He empties whatever remains of his wallet, waves vaguely at new friends he knows won’t wave back, takes one last mental note of the scenery (a vintage Taxi Driver poster, the stools’ faint wear and tear), and glides out the glass doors and on through the dark. Glides, headphone-free, over the courtyard, down the main thoroughfare with the river to his left, and into the Marco Polo lobby—quite literally into, as he’ll learn when he wakes.

He sleeps soundly that night, the sort of sleep so deep it makes you realize you haven’t had a proper one in months. Free, finally, from the gnawing sensation of having been there before. He dreams about gators and sweat-beaded cherubs. About ladies in parks with puffy vests, dancing, and dusty Tsingtaos lit by an iodine glare. He’s leaving that morning in a prepaid cab, but tonight there can only be entrances. Impossible cities, unparsable tongues, wheels down on still-unworn runway.

When the light does finally nudge him awake, it takes a few minutes to piece it all together. The whisky-stained peacoat, the woodchips in his breath, the lump on his forehead from the triple-paned wall. He resists the urge to let it mean something, but it soon gets the better of him. Then he digs into his pocket and answers the phone.

**********

Like most worthwhile ideas, this first one sounds exceedingly obvious: beyond all layers of theory or numb abstraction, when we talk about socioeconomic issues what we’re really talking about is the behavior of people—individuals with irrational feelings, desires, egos. So it stands to reason that small groups of people, brought in close proximity, might embody the same polarizing characteristics we see in our politics.

Like most worthwhile ideas, this first one sounds exceedingly obvious: beyond all layers of theory or numb abstraction, when we talk about socioeconomic issues what we’re really talking about is the behavior of people—individuals with irrational feelings, desires, egos. So it stands to reason that small groups of people, brought in close proximity, might embody the same polarizing characteristics we see in our politics. While a small group of people can reflect society at large, they don’t always reflect it accurately. Particularly when they’re buffered from the outside world. Three films this year used very different tacts to show the way

isolation begets a sort of funhouse mirror, creating a dangerously warped image of reality. Empathetically depicting that distortion field without excusing those who act on it is an inherently risky endeavor. So it shouldn’t be surprising that each of these was met with polarized reactions—often outright controversy—on initial release.

While a small group of people can reflect society at large, they don’t always reflect it accurately. Particularly when they’re buffered from the outside world. Three films this year used very different tacts to show the way

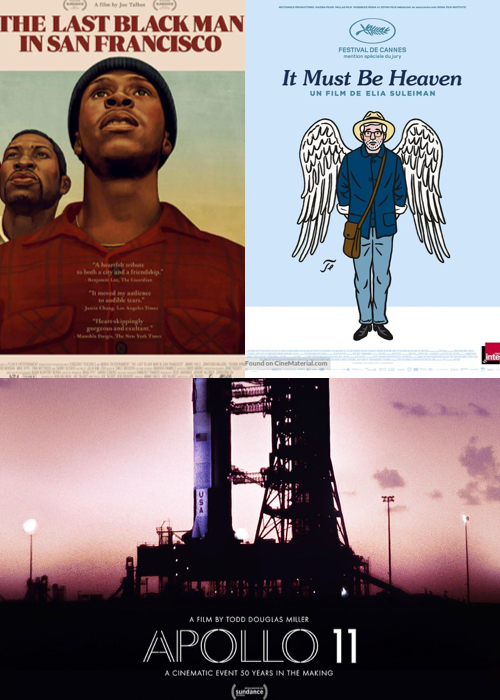

isolation begets a sort of funhouse mirror, creating a dangerously warped image of reality. Empathetically depicting that distortion field without excusing those who act on it is an inherently risky endeavor. So it shouldn’t be surprising that each of these was met with polarized reactions—often outright controversy—on initial release. If art is in constant conversation with society, and society is influenced by the art it consumes, a prolific artist might live long enough to be on both sides of the conversation. In 2019, we saw that phenomenon play out onscreen. Three iconic (and heavily-imitated) directors not only released their best films in years, they grappled with their own creative legacies in the process.

If art is in constant conversation with society, and society is influenced by the art it consumes, a prolific artist might live long enough to be on both sides of the conversation. In 2019, we saw that phenomenon play out onscreen. Three iconic (and heavily-imitated) directors not only released their best films in years, they grappled with their own creative legacies in the process. Still, there’s a reason we glamorize bad behavior: it’s riveting. Whether television celebrity or problematic friend, there’s a certain charisma or allure that comes with damaging behavior. In small doses, that allure can be a vehicle for empathy. Give it too much power, though, and it might pull you down with it.

Still, there’s a reason we glamorize bad behavior: it’s riveting. Whether television celebrity or problematic friend, there’s a certain charisma or allure that comes with damaging behavior. In small doses, that allure can be a vehicle for empathy. Give it too much power, though, and it might pull you down with it. You could make a case that art always hangs around the periphery of death, a subject so universal it’s become a cliché. This year, though, a much more specific idea about mortality was percolating. It has something to with coming to terms with ending one’s life: with rendering it, on some level, a positive choice. And sharing that happysad burden.

You could make a case that art always hangs around the periphery of death, a subject so universal it’s become a cliché. This year, though, a much more specific idea about mortality was percolating. It has something to with coming to terms with ending one’s life: with rendering it, on some level, a positive choice. And sharing that happysad burden. Human connection can’t slow death. Nor can it fix a broken world, cheery slogans notwithstanding. Love has never been an antidote for pain. At its best, though, it can sometimes be a means of sanctifying pain, of rendering shared hardship into a sort of testimony. Four films this year explore the way love can act as a bulwark of warmth against an uncaring world.

Human connection can’t slow death. Nor can it fix a broken world, cheery slogans notwithstanding. Love has never been an antidote for pain. At its best, though, it can sometimes be a means of sanctifying pain, of rendering shared hardship into a sort of testimony. Four films this year explore the way love can act as a bulwark of warmth against an uncaring world. Companionship is a powerful drug. When it’s working, a relationship can ground us, orient us, like nothing in the world. But when it’s misaligned, that same force can prove extremely destabilizing.

Companionship is a powerful drug. When it’s working, a relationship can ground us, orient us, like nothing in the world. But when it’s misaligned, that same force can prove extremely destabilizing. Filmmaking, like macroeconomics, has a certain built-in time delay—with so many variables between concept and execution, it’s hard to trace any neat causal links. So I don’t know when this particular sentiment started; I only know that it hit 2019 like a third act flash flood. It goes like this: unconstrained capitalism is a soul-numbing force.

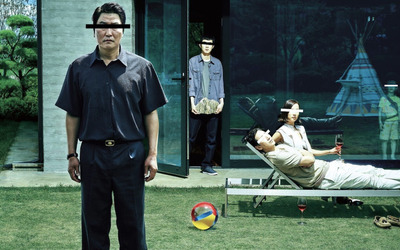

Filmmaking, like macroeconomics, has a certain built-in time delay—with so many variables between concept and execution, it’s hard to trace any neat causal links. So I don’t know when this particular sentiment started; I only know that it hit 2019 like a third act flash flood. It goes like this: unconstrained capitalism is a soul-numbing force.  In a list with no shortage of tenuous connections, this one is the hardest to pinpoint. I’m struggling to put it in words. It isn’t an idea so much as a sensation; a very particular angle of approach. And it has something to do with longing. How certain spaces, when properly framed, seem to call to you even as they push you away. How they carve some entrancing middle ground between attainable and not, instill in you an irrational, pre-emptive nostalgia. It’s no surprise that these films are among the most visually sumptuous of the year. Every still could be a painting. Every painting makes you want.

In a list with no shortage of tenuous connections, this one is the hardest to pinpoint. I’m struggling to put it in words. It isn’t an idea so much as a sensation; a very particular angle of approach. And it has something to do with longing. How certain spaces, when properly framed, seem to call to you even as they push you away. How they carve some entrancing middle ground between attainable and not, instill in you an irrational, pre-emptive nostalgia. It’s no surprise that these films are among the most visually sumptuous of the year. Every still could be a painting. Every painting makes you want. In last year’s list, I saw cinema as a response to trauma—whether an escape, a confession, or an act of defiance. Maybe that was still rattling around in my skull when I sat down in theatres this year. Because for me, in a year jam-packed with fantastic films, the ones that moved me most felt less like storytelling than therapy sessions, working out the damage done by deeply flawed men. Each carried with them a collective exhale; a recognition that, by confronting the past head-on, we might eventually move beyond it.

In last year’s list, I saw cinema as a response to trauma—whether an escape, a confession, or an act of defiance. Maybe that was still rattling around in my skull when I sat down in theatres this year. Because for me, in a year jam-packed with fantastic films, the ones that moved me most felt less like storytelling than therapy sessions, working out the damage done by deeply flawed men. Each carried with them a collective exhale; a recognition that, by confronting the past head-on, we might eventually move beyond it.