More ramblings: Check out my previous end-of-year lists to get a sense of my taste in movies.

Podcast: You can listen to my flat Top 10 list on The Spoiler Warning.

[02/09/2022 Update]: Since writing this, I’ve been fortunate enough to catch up with Red Rocket and Drive My Car, both of which would have landed quite high on this list.

Introduction

“Ill-defined.”

I’ve been struggling to find a phrase to summarize the year, and this is the best I could conjure. If 2020 was synonymous with shared catastrophe, 2021 was a period when everything splintered. There were, of course, the usual bifurcations. Ask a San Francisco leftist and an Orange County libertarian to sum up their experience, and you’re bound to get conflicting feedback. A hypochondriac software engineer and their high-school-teaching neighbor probably won’t fare much better (though they’re markedly less likely to throw punches). The splintering I’m referring to, though, wasn’t a fracture of the body so much as a mass induced mitosis. Left to our own devices after a year of top-down panic, we fashioned for ourselves a thousand inconsistent 2021s. Or at least, that’s how this lefty hypochondriac felt.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was a year of continued lockdown, of days stuck indoors, nursing a when-will-this-shit-end malaise. It was a year of liberation, of rapturous happy hours and outdoor gourmandizing and cross-country trips that felt intergalactic, unreal. It was a year of lingering trauma, of a death toll rising with no end in sight and a populace that lost the will to track it. It was a year of immense personal joys: reunited families, a successful acquisition, multiple weddings (one of which was mine!). It was a sinusoidal cycle of hopes and reversals: bold political promises with less-than-half-assed executions, vaccines and variants, boosters and waves. I spent New Years Eve on the dance floor of a ship in the Antarctic, celebrating our ephemeral togetherness on an empty, melting continent while “Omicron Surges!” buzzed in my pocket and Lou Reed doo-do-dooed us down to midnight under a half-setting sun. It was unspeakably beautiful, but it was so many things.

This was a strange year to be alive and a strange year to be a moviegoer. Anticipated release dates ebbed and flowed without warning; festivals remained strictly virtual till the moment they didn’t. Where once there’d been a definitive, united sense of loss, now each loss was a matter of personal discretion. I would only book a ticket if the theatre was nearly empty. Or rather, if case rates were sufficiently low. No, I would ignore case rates if I had an N95 and refused to buy a drink. Scratch that, I would order a full dinner and eat it at my seat but only if no other patron was within 3 seats of—you get the idea. By and large, I avoided physical screenings as much as possible. Of the 117 new releases I saw this year, only 9 were in a theatre.1 My list of unseen films feels longer than ever, including a slew of December heavy-hitters that only screened theatrically and which I’d deemed too risky to seek out.2 To a spoiled film fanatic living in a major U.S. city, there’s a real cognitive dissonance in tallying just how many I missed.

But if the year was confusing, it was also deceptively strong. Sitting on my flight home shortly after New Years, I couldn’t conceive of scrounging together a Top 10…at least not without enduring a brutal iTunes marathon first. Three days and zero marathons later, I was staring at a shortlist of some 30 titles, wondering how to whittle it down for the evening’s recording session. As I sacrificed darling after darling to the gods of the decimal system, I knew my future write-up was doomed. Not ten films, no, not even ten pairs. A dozen pairs, maybe, if I was willing to be ruthless. I settled on ruthless.

Befitting an “ill-defined” year, there’s no overriding ethos that describes this list. There are crushing dramas and raunchy comedies, major contenders and tiny festival finds, heart-on-your-sleeve indies and musical Turduckens and some that shape-shifted genres with each passing scene. As usual, casualties3 abound and the ranking4 is fuzzy—this is a celebration of good things, not a critique by omission. So let’s make like a thermal graph of the Ross Ice Shelf and dance. Here are my Top 12 Movie Pairings of 2021:

12) Found Families: Language Lessons and Bad Trip ↯

11) Truncated Adolescences: Slalom and The Fallout ↯

10) Tense Gatherings: Spencer and The Humans ↯

9) Deafening Monologues: Bo Burnham: Inside and Tick, Tick…BOOM! ↯

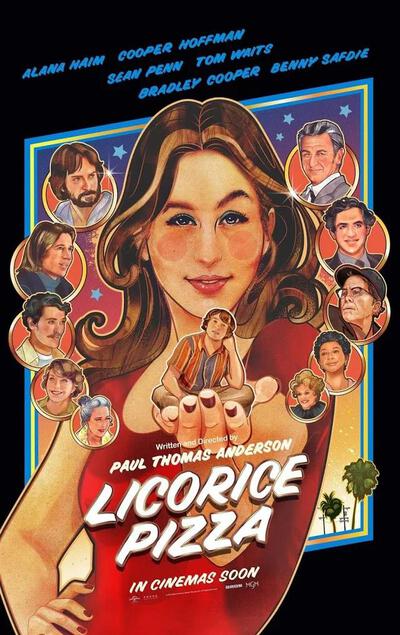

8) Lowering Guardrails: Compartment No. 6 and Licorice Pizza ↯

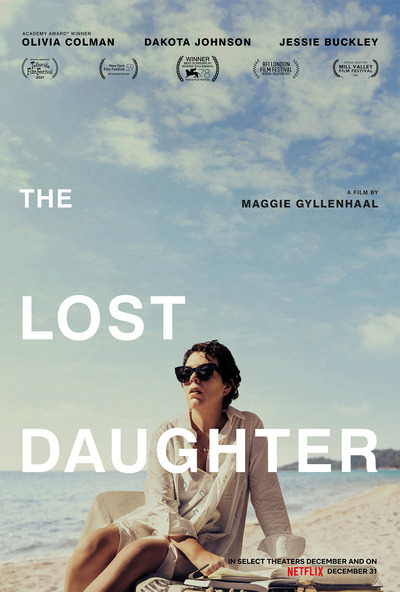

7) Unmet Expectations: The Lost Daughter and Bergman Island ↯

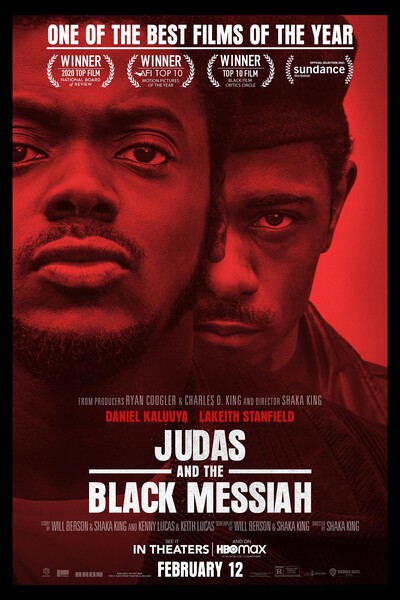

6) Shifting Convictions: The Green Knight and Judas and the Black Messiah ↯

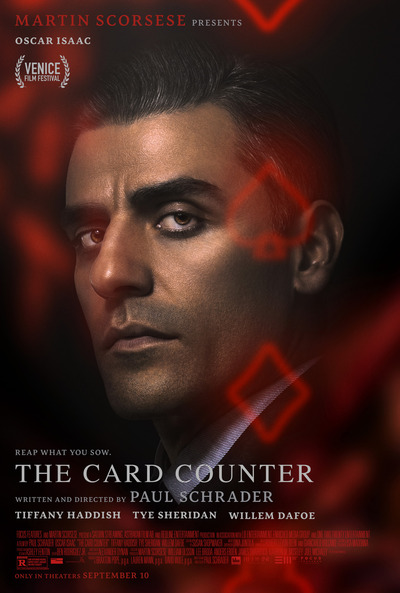

5) Unforgivable Histories: Mass and The Card Counter ↯

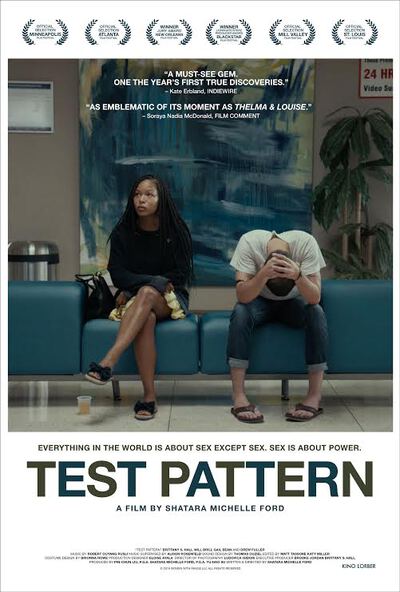

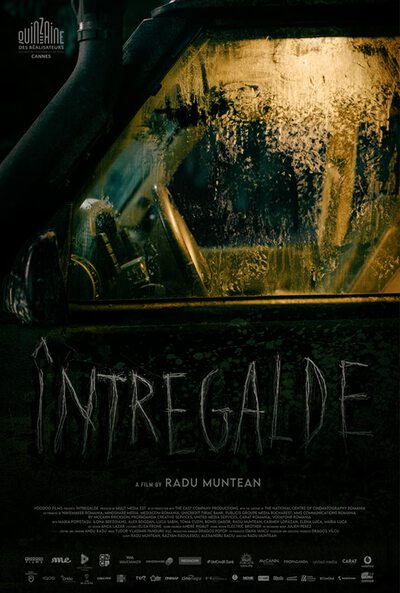

4) Clarifying Crises: Test Pattern and Întregalde ↯

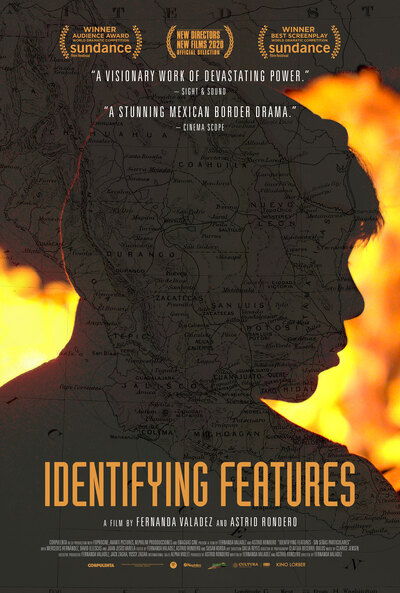

3) Personified Abstractions: Flee and Identifying Features ↯

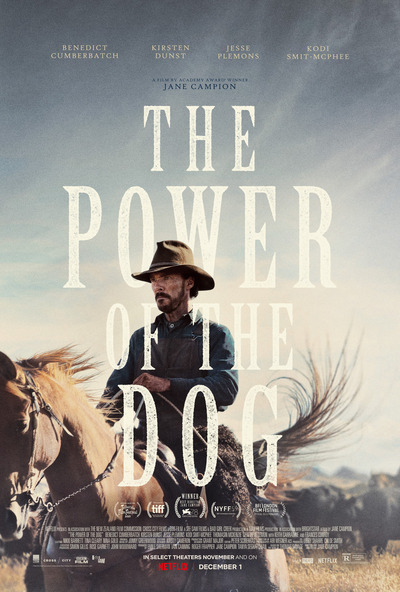

2) Toxic Defenses: The Power of the Dog and The Killing of Two Lovers ↯

1) Present-Tense Memories: C’mon C’mon and Pig ↯

12. Found Families: Language Lessons and Bad Trip

Everything got a bit fuzzier last year, including isolation. Hard-and-fast rules were replaced by an ever-shifting calculus: outdoor only, no more than 2 at a time, a drive but not a flight away, a flight but not a layover. Microweddings, park reunions, cocktails on the roof. With each event carrying some (manageable) risk, the people we opted to share them with became more precious, somehow. Ad hoc, chosen families.

These are stories about choosing other people. They’re love letters to platonic friendships and the chaotic events that rarify them.

Friendship can flourish in the most unexpected places. In Language Lessons, that place is a video chat. Cariño is a Spanish language teacher based in Costa Rica; Adam lives in Oakland with his wealthy, doting husband, who has gifted him a hundred Spanish lessons. What follows is a charming, minimalist drama about human connection. Adam and Cariño’s relationship is defined by limitation: they have never met in person, know nothing of each other’s histories, and the former’s Spanish vocab is childlike at best. Far from being a hindrance, though, those limits only deepen their connection. Truth by way of brevity. There’s a soulful undercurrent to their early lessons together, the way they fumblingly reveal themselves despite their best intentions. We can feel something personal wriggling to break free, made all the more lovely by the struggle.

Friendship can flourish in the most unexpected places. In Language Lessons, that place is a video chat. Cariño is a Spanish language teacher based in Costa Rica; Adam lives in Oakland with his wealthy, doting husband, who has gifted him a hundred Spanish lessons. What follows is a charming, minimalist drama about human connection. Adam and Cariño’s relationship is defined by limitation: they have never met in person, know nothing of each other’s histories, and the former’s Spanish vocab is childlike at best. Far from being a hindrance, though, those limits only deepen their connection. Truth by way of brevity. There’s a soulful undercurrent to their early lessons together, the way they fumblingly reveal themselves despite their best intentions. We can feel something personal wriggling to break free, made all the more lovely by the struggle.

Bad Trip might strike some as an odd inclusion on this list. A hidden camera prank show wrapped in a zany road trip comedy, it’s about as far removed from “minimalist drama” as you can get. On multiple levels, though, this is an earnest ode to companionship and shared…well, let’s just say experiences. Strip away the hilariously R-rated set-pieces and nonsensical plot machinations, and you’re left with a surprisingly sweet saga about two best friends. But it’s the meta story that really pulled me in. There’s something genuinely communal about watching this: It made me feel present with the cast unlike anything else this year. With its anarchic swerving between reality and fiction, Bad Trip implicates the viewer in every manic escalation and dear-god-don’t-tell-me-they’re-gonna twist. It has the cadence of a joke you had to be there to find funny, and a heart that’s big and silly enough to bring us along for the ride.

Bad Trip might strike some as an odd inclusion on this list. A hidden camera prank show wrapped in a zany road trip comedy, it’s about as far removed from “minimalist drama” as you can get. On multiple levels, though, this is an earnest ode to companionship and shared…well, let’s just say experiences. Strip away the hilariously R-rated set-pieces and nonsensical plot machinations, and you’re left with a surprisingly sweet saga about two best friends. But it’s the meta story that really pulled me in. There’s something genuinely communal about watching this: It made me feel present with the cast unlike anything else this year. With its anarchic swerving between reality and fiction, Bad Trip implicates the viewer in every manic escalation and dear-god-don’t-tell-me-they’re-gonna twist. It has the cadence of a joke you had to be there to find funny, and a heart that’s big and silly enough to bring us along for the ride.

11. Truncated Adolescences: Slalom and The Fallout

Despite the popular refrain, nothing actually paused for the pandemic. The days continue to pass, even if they seem to blur together. So I can’t imagine how it would feel to be a teenager in this moment, for whom there can be no illusion of frozen time, no nebulous future “do-over.” To be consciously growing in a world that’s forced to stand still, to come of age in an era defined by acute limitations—it’s an unfathomable, collective loss.

Nothing I’ve seen this year has addressed that (suddenly universal) experience, but two intimate dramas did deal with the profound sadness of truncated youth. They’re about the way that trauma can accelerate or stunt the adolescent experience, and the resilience of those who survive it.

[CW: sexual assault, violence against minors]

Slalom is centered on the perspective of Lyz, a 15-year-old athlete who spends her days training at a remote, Alpine ski academy. She’s independent, motivated, and—under the tutelage of her adult instructor Fred—seems to be on track for greatness.

That sort of internal striving can be its own overwhelming pressure, and Fred amplifies that pressure at every opportunity. But what seems at first blush to be a wintry spin on Whiplash5, instead becomes something darker. Presented to us with harrowing directness, hers is a story of sexual abuse at the hands of a man tasked with supporting her. Thrust into a queasy imitation of adulthood, Lyz attempts to compartmentalize her personal trauma and “professional life.” She’s convinced that the only thing to do is move forward. It’s a shockingly understated, naturalistic depiction, made all the more heartbreaking by her initially muted response. Power structures built on secrecy and trust can condition us to accept the inexcusable. Eventually, the curtain has to fall.

Slalom is centered on the perspective of Lyz, a 15-year-old athlete who spends her days training at a remote, Alpine ski academy. She’s independent, motivated, and—under the tutelage of her adult instructor Fred—seems to be on track for greatness.

That sort of internal striving can be its own overwhelming pressure, and Fred amplifies that pressure at every opportunity. But what seems at first blush to be a wintry spin on Whiplash5, instead becomes something darker. Presented to us with harrowing directness, hers is a story of sexual abuse at the hands of a man tasked with supporting her. Thrust into a queasy imitation of adulthood, Lyz attempts to compartmentalize her personal trauma and “professional life.” She’s convinced that the only thing to do is move forward. It’s a shockingly understated, naturalistic depiction, made all the more heartbreaking by her initially muted response. Power structures built on secrecy and trust can condition us to accept the inexcusable. Eventually, the curtain has to fall.

The Fallout takes a similarly naturalistic tact in its portrait of a different form of trauma. Vada is an eminently clever junior in high school, whose world is undone by a mass shooting at school. Or at least, her family presumes it’s been undone. After coming down from an initial state of shock, what’s most concerning is just how little she’s changed. She has the same deprecating humor, the same easygoing charm, same self-fulfilling insistence that everything is fine. Like Lyz, her instinctive coping strategy is a fake-it-till-you-make-it brand of strength: accept the situation and keep moving. But while her classmates are divided between putting tragedy in the rear-view and channeling their outrage into activism, Vada’s keep-moving intentions leave her firmly stuck in place. She can’t make forward motion until she’s acknowledged that she’s hurting, but to acknowledge it would shatter the only protective tool she has. What I adore about this film is Vada’s beating heart at its center: a cocktail of irony and sincerity, energy and stasis, which feels remarkably true to this moment. Through her struggle to modulate her outlook while retaining that vulnerable core, we see a glimmer of the adult she’s poised to become. If she’s any indication, we have reason to be hopeful.

The Fallout takes a similarly naturalistic tact in its portrait of a different form of trauma. Vada is an eminently clever junior in high school, whose world is undone by a mass shooting at school. Or at least, her family presumes it’s been undone. After coming down from an initial state of shock, what’s most concerning is just how little she’s changed. She has the same deprecating humor, the same easygoing charm, same self-fulfilling insistence that everything is fine. Like Lyz, her instinctive coping strategy is a fake-it-till-you-make-it brand of strength: accept the situation and keep moving. But while her classmates are divided between putting tragedy in the rear-view and channeling their outrage into activism, Vada’s keep-moving intentions leave her firmly stuck in place. She can’t make forward motion until she’s acknowledged that she’s hurting, but to acknowledge it would shatter the only protective tool she has. What I adore about this film is Vada’s beating heart at its center: a cocktail of irony and sincerity, energy and stasis, which feels remarkably true to this moment. Through her struggle to modulate her outlook while retaining that vulnerable core, we see a glimmer of the adult she’s poised to become. If she’s any indication, we have reason to be hopeful.

10. Tense Gatherings: Spencer and The Humans

It was a year of reunions, for better or worse. While everyone I know has a perfectly frictionless relationship with their family6, I..ehrm…imagine this may not always be the case. I mean, it stands to reason that someone, somewhere, must have felt a wisp of discomfort when (after a full year of neatly-delineated Zoom calls) they found themselves sitting shoulder to shoulder around a dining room table, swapping the same stale air and recycled talking points, trying to improvise pleasant conversation while a politicized virus exacerbated existing divides in a meteorologically manic, legislatively impotent country where a full third of the voting population can’t even agree on the legitimacy of an audited election let alone a multi-decade strategy for curbing CO₂ and how the hell did we make eye contact with an entire group at—

Where was I?

These films explore the pressure of a tense holiday gathering: festering conflicts, dredged up histories, and the external stressors they so often conjure by proxy. Both set in creaky, haunting places, they serve as literal manifestations of a claustrophobic mind.

In Spencer, Princess Diana is dealing with a host of pressures. There’s the overbearing family that police her every move, the vulture-like prowling of the British tabloid press, and the emotionally frigid husband who only makes both matters worse. Over a three-day Christmas visit to their royal estate, she is physically and emotionally trapped. Forced to dress lavishly but never provocatively, to eat indulgently as performance (despite her struggles with food), to pantomime “transparency” without showing a modicum of pain. Hers is a haunted house within a haunted house. She’s holed up in a mansion whose curtains are literally sewn shut, and she can’t escape the confines of her head—an inner voice (and outer Anne Boleyn) that insists her plight is preordained. When she finally does break free of both in service to a miracle, it’s a shared release of tension unlike any I’ve seen this year.

In Spencer, Princess Diana is dealing with a host of pressures. There’s the overbearing family that police her every move, the vulture-like prowling of the British tabloid press, and the emotionally frigid husband who only makes both matters worse. Over a three-day Christmas visit to their royal estate, she is physically and emotionally trapped. Forced to dress lavishly but never provocatively, to eat indulgently as performance (despite her struggles with food), to pantomime “transparency” without showing a modicum of pain. Hers is a haunted house within a haunted house. She’s holed up in a mansion whose curtains are literally sewn shut, and she can’t escape the confines of her head—an inner voice (and outer Anne Boleyn) that insists her plight is preordained. When she finally does break free of both in service to a miracle, it’s a shared release of tension unlike any I’ve seen this year.

No paparazzi are spying on the family in The Humans. But as they celebrate Thanksgiving in their daughter’s Chinatown apartment, it’s hard not to feel that same whiff of performance. They are happy to be together; happy to meet the new boyfriend; happy to finally catch up on one another’s lives. When it comes time to communicate, though, everything is strained. Their conversations hit all the usual nerves: political fissures, jabs about finances, closed-minded quips that land with a thud. There are other nerves, too, unspoken relational wounds they seemingly can’t help but pick at. Here, the haunted house aspect is rendered surprisingly literal. Unplaceable noises, flickering lights, clumps of paint and water damage which appear metastatic, looming. The apartment functions both as a symbol of their discomfort and as an active, taunting participant: luring different pairs away from the group, lulling them into a false sense of security, betraying them with its lurches and paper-thin walls.

No paparazzi are spying on the family in The Humans. But as they celebrate Thanksgiving in their daughter’s Chinatown apartment, it’s hard not to feel that same whiff of performance. They are happy to be together; happy to meet the new boyfriend; happy to finally catch up on one another’s lives. When it comes time to communicate, though, everything is strained. Their conversations hit all the usual nerves: political fissures, jabs about finances, closed-minded quips that land with a thud. There are other nerves, too, unspoken relational wounds they seemingly can’t help but pick at. Here, the haunted house aspect is rendered surprisingly literal. Unplaceable noises, flickering lights, clumps of paint and water damage which appear metastatic, looming. The apartment functions both as a symbol of their discomfort and as an active, taunting participant: luring different pairs away from the group, lulling them into a false sense of security, betraying them with its lurches and paper-thin walls.

9. Deafening Monologues: Bo Burnham: Inside and Tick, Tick…BOOM

It doesn’t take a group to conjure emotional claustrophobia. Some of us are perfectly capable of doing it on our own. Stuck inside a room with the world at our fingertips, we’ve never had so many inputs or so few (productive) outlets. That nagging inner voice that says “You should be doing more,” it doesn’t check for healthy exits before filling mental space.

These films explore the tick, tick, ticking that spurs us to action, and the ways that drive, absent an egress, can bend inward on itself. We follow two creatives turning 30 at the turn of the decade, who question the value of the art they create until the questioning melds with the creation.

When analyzing the year via the movies it produced, Bo Burnham: Inside almost feels like a cheat. A hybrid comedy special/performance art piece shot and set entirely in the pandemic, communicating “how it felt” is its overriding point. That it communicates it so deftly would, alone, merit inclusion on this list: Scroll through TikTok and find me any other work that so clearly struck a nerve. But what really sets the special apart for me is how well it speaks to the non-pandemic aspects. The character of Bo Burnham (and this is very much a character) lives in a world that is somehow post -irony and -sincerity. Overwhelmed by an amalgamation of contradictory inputs, the quickest way to express the truth is to present competing versions: the backlash to the backlash to the thing that’s just begun. He’s rendered impotent by excess, too clever not to undercut every attempt at honest sentiment, too consumed by anxious energy to resist attempting it regardless. He wants to make comedy, but comedy is inherently egocentric. He wants to verbalize the rot at the heart of Internet-era culture, but he is a shareholder in and influencer of that culture. A confessional style is masturbatory and a failure to confess is wrong; apathy’s a tragedy and boredom is a crime. And so he spirals ever deeper into his bespoke, relentless Everything, shedding casual bits of brilliance as he goes.

When analyzing the year via the movies it produced, Bo Burnham: Inside almost feels like a cheat. A hybrid comedy special/performance art piece shot and set entirely in the pandemic, communicating “how it felt” is its overriding point. That it communicates it so deftly would, alone, merit inclusion on this list: Scroll through TikTok and find me any other work that so clearly struck a nerve. But what really sets the special apart for me is how well it speaks to the non-pandemic aspects. The character of Bo Burnham (and this is very much a character) lives in a world that is somehow post -irony and -sincerity. Overwhelmed by an amalgamation of contradictory inputs, the quickest way to express the truth is to present competing versions: the backlash to the backlash to the thing that’s just begun. He’s rendered impotent by excess, too clever not to undercut every attempt at honest sentiment, too consumed by anxious energy to resist attempting it regardless. He wants to make comedy, but comedy is inherently egocentric. He wants to verbalize the rot at the heart of Internet-era culture, but he is a shareholder in and influencer of that culture. A confessional style is masturbatory and a failure to confess is wrong; apathy’s a tragedy and boredom is a crime. And so he spirals ever deeper into his bespoke, relentless Everything, shedding casual bits of brilliance as he goes.

A film adaptation of a stage adaptation of Jonathan Larsen’s one man show, Tick, Tick…BOOM is a Jenga tower built with similar materials. Check the scoreboard: an artist whose birthday is cause for existential panic, a self-referential musical which details the author’s creative process, a deadly (and politicized) pandemic which makes that process feel limp and narcissistic, a generation numbed by an “empty image emanating out of a screen.” When he was 27, Bo’s grandpa fought in Vietnam; when Sondheim was 27, he debuted West Side Story. But while both artists use reflection to convey inner turmoil, they do so in remarkably different ways. Burnham’s hall of mirrors is solitary, downbeat, a dim-lit exorcism of irreconcilable things. Whereas Larsen’s is all bright augmentation, a joyous spiraling upwards. It’s a vocal chorus rising when every instinct says “Resolve!” Consider the standout sequence “Therapy,” one block of the tower at a time. Past-tense Jonathan is in a fight with his girlfriend over a song he hasn’t yet written about her, while present-tense Jonathan performs said song with a partner as her stand-in. The in-song couple wear withering smiles undercut by the insults they’re hurling, but through their facade of thinly-suppressed outrage gleams the performers’ delight at selling the bit.7 All of their layers are swaying in concert, flailing through contradictions. None of them will be untangled: Larsen’s litany of questions, his Post-It Note “Why”s, they remain unanswered after curtains close. It’s no matter: he’ll belt them out with the cadence of an exuberant conclusion.

A film adaptation of a stage adaptation of Jonathan Larsen’s one man show, Tick, Tick…BOOM is a Jenga tower built with similar materials. Check the scoreboard: an artist whose birthday is cause for existential panic, a self-referential musical which details the author’s creative process, a deadly (and politicized) pandemic which makes that process feel limp and narcissistic, a generation numbed by an “empty image emanating out of a screen.” When he was 27, Bo’s grandpa fought in Vietnam; when Sondheim was 27, he debuted West Side Story. But while both artists use reflection to convey inner turmoil, they do so in remarkably different ways. Burnham’s hall of mirrors is solitary, downbeat, a dim-lit exorcism of irreconcilable things. Whereas Larsen’s is all bright augmentation, a joyous spiraling upwards. It’s a vocal chorus rising when every instinct says “Resolve!” Consider the standout sequence “Therapy,” one block of the tower at a time. Past-tense Jonathan is in a fight with his girlfriend over a song he hasn’t yet written about her, while present-tense Jonathan performs said song with a partner as her stand-in. The in-song couple wear withering smiles undercut by the insults they’re hurling, but through their facade of thinly-suppressed outrage gleams the performers’ delight at selling the bit.7 All of their layers are swaying in concert, flailing through contradictions. None of them will be untangled: Larsen’s litany of questions, his Post-It Note “Why”s, they remain unanswered after curtains close. It’s no matter: he’ll belt them out with the cadence of an exuberant conclusion.

8. Lowering Guardrails: Compartment No. 6 and Licorice Pizza

If shared space can be a catalyst for internal division, it can also be a venue for emotional release. Whether we wear each other down or we build each other up, proximity chips away at our instinctual defenses. When circumstance partitions us into tiny bubbles, who will be drawn closer and who will be repelled? It isn’t always clear on first inspection.

Impressions aren’t always what they seem. Two endearing films explored what we release through shared experience, the ways we soften to each other over time.

Compartment No. 6 is in no hurry to reveal its destination. The story of two young travelers who find each other on a trans-Siberian train, it’s bound to court comparisons to Richard Linklater. But in truth, their situation shares less with Delpy and Hawke than it does Steve Martin and John Candy. When Laura first meets Ljoha, he seems genuinely abrasive. He downs untold shots of vodka, trespasses over every personal boundary, and carries himself with an air of volatility and menace. Or, at least, that’s how he’s perceived by his companion. The magic of this film is just how nimbly it pulls the rug out from under you—despite also, overtly, calling its shot. I love the way it conveys the wistful openness of travel, that irrepressible desire to bare your soul to a stranger. Barreling through the Russian countryside in their sardine-packed enclosure, Laura and Ljoha slowly start to melt.

Compartment No. 6 is in no hurry to reveal its destination. The story of two young travelers who find each other on a trans-Siberian train, it’s bound to court comparisons to Richard Linklater. But in truth, their situation shares less with Delpy and Hawke than it does Steve Martin and John Candy. When Laura first meets Ljoha, he seems genuinely abrasive. He downs untold shots of vodka, trespasses over every personal boundary, and carries himself with an air of volatility and menace. Or, at least, that’s how he’s perceived by his companion. The magic of this film is just how nimbly it pulls the rug out from under you—despite also, overtly, calling its shot. I love the way it conveys the wistful openness of travel, that irrepressible desire to bare your soul to a stranger. Barreling through the Russian countryside in their sardine-packed enclosure, Laura and Ljoha slowly start to melt.

Regardless of The Discourse or the film’s ostensible plot, I don’t view Licorice Pizza as a romance. It doesn’t deal in lovelorn glances, revealing confessions, intimacies liable to linger. No, the image I’m left with is Alana Kane’s smirk: complicit in something she’s been told is beneath her, bemused in spite of her better judgement. The object of her bemusement is Gary Valentine, the brash-talking, 15-year-old huckster-in-training who has gotten them into yet another ridiculous bind. What draws me to this movie is similar to the draw of Bad Trip: it carries us along in its hijinks. It lets us roll with its mischief. As the pair schemes their way through a 1970s San Fernando Valley, we feel the zig-zag of affection and resentment, giddiness and disgust, that defines both young adulthood and mid-adolescence. The characters are far from perfect, and the script has a few truly baffling flaws.8 But beneath the discomfort and nostalgic set dressing is a story about the thrill of being seen.

Regardless of The Discourse or the film’s ostensible plot, I don’t view Licorice Pizza as a romance. It doesn’t deal in lovelorn glances, revealing confessions, intimacies liable to linger. No, the image I’m left with is Alana Kane’s smirk: complicit in something she’s been told is beneath her, bemused in spite of her better judgement. The object of her bemusement is Gary Valentine, the brash-talking, 15-year-old huckster-in-training who has gotten them into yet another ridiculous bind. What draws me to this movie is similar to the draw of Bad Trip: it carries us along in its hijinks. It lets us roll with its mischief. As the pair schemes their way through a 1970s San Fernando Valley, we feel the zig-zag of affection and resentment, giddiness and disgust, that defines both young adulthood and mid-adolescence. The characters are far from perfect, and the script has a few truly baffling flaws.8 But beneath the discomfort and nostalgic set dressing is a story about the thrill of being seen.

7. Unmet Expectations: The Lost Daughter and Bergman Island

It’s the thought of what could have been that gets you. The hopes we’d outlined for our lives, the dreams that get deflated. Two years into this thing, I still struggle to reconcile my image of the future with the reality we’ve been handed.

So let’s travel to that wellspring of unmet expectations: a summer vacation. Two mothers head to an idyllic, coastal paradise, where they find themselves confronted by an imperfect present, and retreat into the path not chosen.

Or, in the case of Leda, a kaleidoscope of paths both chosen and not. The Lost Daughter is one of those beguiling viewing experiences best left unsullied, so I won’t reveal where those potential paths are headed. Instead, I’ll simply walk you through the premise. Leda is a middle-aged professor of comparative literature, visiting a beachside Italian town on a working holiday. Her attempts to relax are continually disrupted, either by her less-than-ideal accommodations (mold in the fruit bowl, cicadas in the bedroom) or, worse, by the uncontrollable behavior of other people. When a young mother and her screaming daughter set up camp on the beach beside her, something internal is jostled loose. What follows is a story about stifled dreams, difficult choices, and the degree to which disillusionment is held up as a virtue. The truism says we don’t always get what we want, but is that a moral imperative or a failure of imagination?

Or, in the case of Leda, a kaleidoscope of paths both chosen and not. The Lost Daughter is one of those beguiling viewing experiences best left unsullied, so I won’t reveal where those potential paths are headed. Instead, I’ll simply walk you through the premise. Leda is a middle-aged professor of comparative literature, visiting a beachside Italian town on a working holiday. Her attempts to relax are continually disrupted, either by her less-than-ideal accommodations (mold in the fruit bowl, cicadas in the bedroom) or, worse, by the uncontrollable behavior of other people. When a young mother and her screaming daughter set up camp on the beach beside her, something internal is jostled loose. What follows is a story about stifled dreams, difficult choices, and the degree to which disillusionment is held up as a virtue. The truism says we don’t always get what we want, but is that a moral imperative or a failure of imagination?

Bergman Island is a similarly slippery work of art. Chris and her partner Tony are independent filmmakers, spending an extended stay on Fårö as they noodle on their scripts. Their Baltic destination, as the title suggests, was immortalized by the films of Ingmar Bergman. Flocks of tourists gather there to idolize his work. But while Tony sees Bergman’s chilly genius as a virtue to be emulated, Chris interrogates the qualities that separate her from both acclaimed men. As the screenplay she writes begins to blur with reality, we’re given access to something, though we can’t quite put a finger on it. A life she longs for but is unable to have? A history which circumstance confined to a footnote? Or is it purely a work of fiction, her characters melding with the desires that inspired them? There are subtle answers to be found as the story progresses, but that reality is hardly the point. The point is the longing that evades intellectual probing, the beauty and risk of an unguarded nerve.

Bergman Island is a similarly slippery work of art. Chris and her partner Tony are independent filmmakers, spending an extended stay on Fårö as they noodle on their scripts. Their Baltic destination, as the title suggests, was immortalized by the films of Ingmar Bergman. Flocks of tourists gather there to idolize his work. But while Tony sees Bergman’s chilly genius as a virtue to be emulated, Chris interrogates the qualities that separate her from both acclaimed men. As the screenplay she writes begins to blur with reality, we’re given access to something, though we can’t quite put a finger on it. A life she longs for but is unable to have? A history which circumstance confined to a footnote? Or is it purely a work of fiction, her characters melding with the desires that inspired them? There are subtle answers to be found as the story progresses, but that reality is hardly the point. The point is the longing that evades intellectual probing, the beauty and risk of an unguarded nerve.

6. Shifting Convictions: The Green Knight and Judas and the Black Messiah

There’s a rallying effect that comes from having clearly-defined enemies: an election to win, an ethos to rebuke, the clarifying focus of a personified threat. The truth that comes after is considerably less exciting: betrayed ideals, disillusioned supporters, crowdsourced moral compasses as cover for inaction.

In a world that throws conventional wisdoms out like chaff, which should we follow? Where are we aiming? These stories are about internal moral reckonings: characters attempting to pen their own legacies while being pulled in competing directions.

The Green Knight is less a hero’s journey than it is a deconstruction of the concept. Gawain has yet to prove his valor, and so he’s set upon a quest. After lobbing off the titular villain’s head last Christmas, he now must travel to his victim’s lair to receive the same blow in kind. There’s no damsel to rescue, no romanticized end goal. Honor compels him, thus he will go. He’s a living reductio ad absurdum: a man hurtling towards his presumable death in pursuit of an amorphous concept. The story is amorphous and dreamlike in turn, questioning every detail. Is there a mythical King Arthur slaying thousands by hand, or a frail, fragile husk commanding fields full of corpses? Is chastity a virtue to be championed or an act of arrogance, withholding? If a knight is slain in a forest and there’s no witness to observe it, where do all his chivalric moral quandaries go?

The Green Knight is less a hero’s journey than it is a deconstruction of the concept. Gawain has yet to prove his valor, and so he’s set upon a quest. After lobbing off the titular villain’s head last Christmas, he now must travel to his victim’s lair to receive the same blow in kind. There’s no damsel to rescue, no romanticized end goal. Honor compels him, thus he will go. He’s a living reductio ad absurdum: a man hurtling towards his presumable death in pursuit of an amorphous concept. The story is amorphous and dreamlike in turn, questioning every detail. Is there a mythical King Arthur slaying thousands by hand, or a frail, fragile husk commanding fields full of corpses? Is chastity a virtue to be championed or an act of arrogance, withholding? If a knight is slain in a forest and there’s no witness to observe it, where do all his chivalric moral quandaries go?

Perhaps the most surprising element of Judas and the Black Messiah is the proportion of screen time devoted to Judas. The Messiah, Fred Hampton, knows exactly where he stands. Recognizing that the powers that be are morally corrupt, he commands a righteous opposition. That war is waged not just through language—though his speeches are electric—but via physical confrontation, if the moment demands it. There’s a gravitational force to everything he does; he pulls us into his orbit. Yet rather than have us view him directly, we watch him through the eyes of Bill O’Neal. Not quite a conman and not quite a disciple, Bill is a wellspring of contradictory impulses and self-justifications. He is, in no uncertain terms, a traitor to the Black Panthers: an FBI informant and a raging egomaniac who will say and do whatever serves him best. But he also feels genuinely emboldened by the movement he’s betraying, seems proud to identify with Fred Hampton’s words. He’s a shape-shifter, an enigma who ping-pongs between clear recognition that “the Law” is unjust, and a desire to wield it, to sanctify his selfishness by it. And in that sense, he is sadly familiar. If decades of status quo enforcement embellished by hope-and-change rhetoric have taught us anything, it’s that Hampton—not O’Neal—was the outlier.

Perhaps the most surprising element of Judas and the Black Messiah is the proportion of screen time devoted to Judas. The Messiah, Fred Hampton, knows exactly where he stands. Recognizing that the powers that be are morally corrupt, he commands a righteous opposition. That war is waged not just through language—though his speeches are electric—but via physical confrontation, if the moment demands it. There’s a gravitational force to everything he does; he pulls us into his orbit. Yet rather than have us view him directly, we watch him through the eyes of Bill O’Neal. Not quite a conman and not quite a disciple, Bill is a wellspring of contradictory impulses and self-justifications. He is, in no uncertain terms, a traitor to the Black Panthers: an FBI informant and a raging egomaniac who will say and do whatever serves him best. But he also feels genuinely emboldened by the movement he’s betraying, seems proud to identify with Fred Hampton’s words. He’s a shape-shifter, an enigma who ping-pongs between clear recognition that “the Law” is unjust, and a desire to wield it, to sanctify his selfishness by it. And in that sense, he is sadly familiar. If decades of status quo enforcement embellished by hope-and-change rhetoric have taught us anything, it’s that Hampton—not O’Neal—was the outlier.

5. Unforgivable Histories: Mass and The Card Counter

Some tragedies run too deep to resolve. Too enormous to express, too immediate to ignore, they defy every narrative convention.

In a year still heavy with incalculable loss, these films leverage spiritual imagery to probe at our collective conscience. What options are there after the unthinkable? How can we approach inconceivable suffering? And how can we reconcile our culpability in it?

Mass functions less as a parable than as a therapy session. Two sets of parents congregate in the basement of a parish. Their goal is, quite simply, to talk. The film doesn’t tell us what they’ve gathered to discuss, and I’d suggest you go in with a similarly blank slate. The beautiful paradox of Mass is that it manages to express something deeper than words, entirely through the medium of four people speaking. They share stories; they argue; they shed many, many tears. It’s difficult at some points to take. But there’s a profound empowerment in seeing it through, an impossible sense of uplift. To experience Mass is to bear witness to something essential, and utterly impervious to melodrama. It’s the human spirit revealing itself on a screen, commanding everything within it to find closure.

Mass functions less as a parable than as a therapy session. Two sets of parents congregate in the basement of a parish. Their goal is, quite simply, to talk. The film doesn’t tell us what they’ve gathered to discuss, and I’d suggest you go in with a similarly blank slate. The beautiful paradox of Mass is that it manages to express something deeper than words, entirely through the medium of four people speaking. They share stories; they argue; they shed many, many tears. It’s difficult at some points to take. But there’s a profound empowerment in seeing it through, an impossible sense of uplift. To experience Mass is to bear witness to something essential, and utterly impervious to melodrama. It’s the human spirit revealing itself on a screen, commanding everything within it to find closure.

If Mass moves us by speaking the unspeakable, The Card Counter stirs us with silence. William Tell is a man of few words. The convict-turned-professional-gambler has so thoroughly narrowed the scope of his life that it feels like religious observance: He enters a casino, plays hours of poker, then returns to an empty hotel room, where, having covered every surface in muted grey sheets, he proceeds to write down his thoughts in a journal. What he’s dwelling on is, again, best discovered for yourself. But when he meets two other wanderers, he feels the hint of an offramp. In La Linda, the liaison for a group of financial backers, he sees an emotional substitute for confession. And in Cirk, his young protege, he sees a chance at redemption, of cultivating a better future than the one he’s been dealt. As he pours himself into both vessels of hope, we’re drawn deeper into his tormented psyche. It’s a hypnotic, slow motion shattering.

If Mass moves us by speaking the unspeakable, The Card Counter stirs us with silence. William Tell is a man of few words. The convict-turned-professional-gambler has so thoroughly narrowed the scope of his life that it feels like religious observance: He enters a casino, plays hours of poker, then returns to an empty hotel room, where, having covered every surface in muted grey sheets, he proceeds to write down his thoughts in a journal. What he’s dwelling on is, again, best discovered for yourself. But when he meets two other wanderers, he feels the hint of an offramp. In La Linda, the liaison for a group of financial backers, he sees an emotional substitute for confession. And in Cirk, his young protege, he sees a chance at redemption, of cultivating a better future than the one he’s been dealt. As he pours himself into both vessels of hope, we’re drawn deeper into his tormented psyche. It’s a hypnotic, slow motion shattering.

4. Clarifying Crises: Test Pattern and Întregalde

Calamity has a way of revealing certain truths: cracks in the armor, private or systemic. Our knee-jerk reactions give lie to our stated ideals; structures we’ve erected often buckle under pressure.

These films deal with clarifying crises, and the acute way they shift our perspectives—magnifying hidden emotional frailties, rendering social abstractions immediate and personal.

[CW: sexual assault]

Test Pattern is a damning social critique, and a remarkably effective one at that. Renesha is a self-possessed Black woman eager to climb the corporate ladder; Evan’s a mellow White tattoo artist who seems content to cheer her on. The film documents two days in the couple’s life: an evening when Renesha is assaulted by a stranger, and the morning after, as she and Evan try for hours to find a rape kit. It’s an excoriating portrait of the indignities we force survivors of assault to endure, the litany of bureaucratic roadblocks that seem designed to hinder hope. But the brilliance of the film also lies in its specific characterizations, in the interpersonal fissures their experience reveals. At first, Evan appears to be a paragon of supportive partnerhood: He tends to Renesha’s immediate needs, believes her story without question, and reiterates his commitment to protect her. He leaps into action in service to the woman whom he loves. But as his instinct towards action grows increasingly desperate, a troubling dynamic develops—one that tiptoes the line between support and ownership, between protection as loving impulse and as assertion of control. Through flashbacks that juxtapose their present day dynamic and their history as a couple, we are asked to recontextualize their relationship through the lenses of race, gender, and ultimately power. It’s a sobering (and brutally recognizable) portrayal, one that defies easy answers and didactic conclusions.

Test Pattern is a damning social critique, and a remarkably effective one at that. Renesha is a self-possessed Black woman eager to climb the corporate ladder; Evan’s a mellow White tattoo artist who seems content to cheer her on. The film documents two days in the couple’s life: an evening when Renesha is assaulted by a stranger, and the morning after, as she and Evan try for hours to find a rape kit. It’s an excoriating portrait of the indignities we force survivors of assault to endure, the litany of bureaucratic roadblocks that seem designed to hinder hope. But the brilliance of the film also lies in its specific characterizations, in the interpersonal fissures their experience reveals. At first, Evan appears to be a paragon of supportive partnerhood: He tends to Renesha’s immediate needs, believes her story without question, and reiterates his commitment to protect her. He leaps into action in service to the woman whom he loves. But as his instinct towards action grows increasingly desperate, a troubling dynamic develops—one that tiptoes the line between support and ownership, between protection as loving impulse and as assertion of control. Through flashbacks that juxtapose their present day dynamic and their history as a couple, we are asked to recontextualize their relationship through the lenses of race, gender, and ultimately power. It’s a sobering (and brutally recognizable) portrayal, one that defies easy answers and didactic conclusions.

Întregalde pulls off a similar trick in reverse, hiding a damning portrait of society under the trappings of an intimate horror. We follow a group of Romanian aid workers as they drive through rural Transylvania, faithfully delivering goods to those in need. Naturally, they believe themselves to be fundamentally decent: They’ve chosen to volunteer when they could be doing otherwise, to devote their precious time to altruistic pursuits. But when a roadside hitchhiker gives them faulty directions, their lofty ideals start to crumble. They become lost and desperate; their relationships fray; the goal pivots from aid to survival. By nightfall, the very same people they’ve traveled to uplift appear to them as either obstacles or threats. Shrewd, unflinching, and perfectly calibrated, the thriller hooked me from beginning to end. In its closing few minutes, though, it became about something more transcendent: the aching reality of humanitarian crises, and how little they match our rose-tinted projections. We may genuinely care about doing “the right thing,” and we may even be willing to suffer for it—that is, if the suffering has predefined bounds, a controllable burn that feels righteous. But are we willing to embrace the daily tedium, the unpredictable discomforts and unrecognized sacrifices that meaningful, protracted change demands?

Întregalde pulls off a similar trick in reverse, hiding a damning portrait of society under the trappings of an intimate horror. We follow a group of Romanian aid workers as they drive through rural Transylvania, faithfully delivering goods to those in need. Naturally, they believe themselves to be fundamentally decent: They’ve chosen to volunteer when they could be doing otherwise, to devote their precious time to altruistic pursuits. But when a roadside hitchhiker gives them faulty directions, their lofty ideals start to crumble. They become lost and desperate; their relationships fray; the goal pivots from aid to survival. By nightfall, the very same people they’ve traveled to uplift appear to them as either obstacles or threats. Shrewd, unflinching, and perfectly calibrated, the thriller hooked me from beginning to end. In its closing few minutes, though, it became about something more transcendent: the aching reality of humanitarian crises, and how little they match our rose-tinted projections. We may genuinely care about doing “the right thing,” and we may even be willing to suffer for it—that is, if the suffering has predefined bounds, a controllable burn that feels righteous. But are we willing to embrace the daily tedium, the unpredictable discomforts and unrecognized sacrifices that meaningful, protracted change demands?

3. Personified Abstractions: Flee and Identifying Features

There’s a point at which the numbness kicks in. One thousand, ten thousand, a hundred thousand, eight. Some defense mechanism rallies to action, inventing new ways to quarantine anguish. We reduce it to a statistic, debate it as a trend, neutralize it as a foregone conclusion. Although it isn’t possible to internalize the enormity of suffering, it’s vital to stay tethered to reality.

Ebert famously referred to film as “a machine that generates empathy.” To me, it’s a machine that reverses that instinctual process of abstraction. At its best, film transports us into a state of mind where everything is personal and unerringly specific, lending experiential weight to intellectualized concepts. With narrative structures that submerge the viewer beneath objective description, these films refuse to be held at a distance.

Amin, the subject of the documentary Flee, has been given every reason to keep his story buried. An Afghan refugee now living in Denmark, there’s a certain precarity built into every moment—a fear that everything might crumble if he’s held up to the light. Which is what makes this such a courageous testimony and such a moving work of art. By use of animation (and a host of voice actors), Flee is able to mask incriminating details while bringing Amin’s childhood memories to life. Fluid, impressionistic, and subjective by design, it communicates emotional undercurrents mere depiction would obscure. Much of this is heartbreaking, though not always in the manner we’ve been primed to expect. We’re reminded that “refugee crisis” is a blanket term, covering countless complex individuals, and that suffering doesn’t operate on relative scales. No statistic could encompass Amin’s reality.

Amin, the subject of the documentary Flee, has been given every reason to keep his story buried. An Afghan refugee now living in Denmark, there’s a certain precarity built into every moment—a fear that everything might crumble if he’s held up to the light. Which is what makes this such a courageous testimony and such a moving work of art. By use of animation (and a host of voice actors), Flee is able to mask incriminating details while bringing Amin’s childhood memories to life. Fluid, impressionistic, and subjective by design, it communicates emotional undercurrents mere depiction would obscure. Much of this is heartbreaking, though not always in the manner we’ve been primed to expect. We’re reminded that “refugee crisis” is a blanket term, covering countless complex individuals, and that suffering doesn’t operate on relative scales. No statistic could encompass Amin’s reality.

If Flee is a documentary that moves with the fluidity of fiction, Identifying Features is a work of ethereal fiction that hits with the weight of documentary. Magdalena’s son, Jesús, set off from home to cross the U.S. border. But in the intervening months, she has yet to hear a word. If the silence is deafening, the news that follows it is worse: The body of Jesús’ traveling companion has been positively identified. Like far too many real-world emigrants, he perished on the journey. No cause of death is given, nor is its absence noted: It’s as if this simply happened, like some stochastic social tax. Thus begins a somber quest, as Magdalena heads north in search of closure. What’s stunning about the experience is how little a window we are offered. She rides the bus in silence; she waits patiently in line; she leafs through photographs of bodies and possessions with methodical persistence. Rather than expressing grief outright, we are made to absorb it through osmosis: through wordless exchanges, sparse encounters, landscapes thrumming with negative space. One particularly stunning scene involves a second-hand memory, foggy and uncertain, as dreamlike as any drawn in Flee. But the details of this memory remain (intentionally) untranslated, narrated in an indigenous tongue Magdalena doesn’t speak. Absent the symbolic, the abstract finality of language, we can only connect by way of feeling. We receive, instead, precisely what we must.

If Flee is a documentary that moves with the fluidity of fiction, Identifying Features is a work of ethereal fiction that hits with the weight of documentary. Magdalena’s son, Jesús, set off from home to cross the U.S. border. But in the intervening months, she has yet to hear a word. If the silence is deafening, the news that follows it is worse: The body of Jesús’ traveling companion has been positively identified. Like far too many real-world emigrants, he perished on the journey. No cause of death is given, nor is its absence noted: It’s as if this simply happened, like some stochastic social tax. Thus begins a somber quest, as Magdalena heads north in search of closure. What’s stunning about the experience is how little a window we are offered. She rides the bus in silence; she waits patiently in line; she leafs through photographs of bodies and possessions with methodical persistence. Rather than expressing grief outright, we are made to absorb it through osmosis: through wordless exchanges, sparse encounters, landscapes thrumming with negative space. One particularly stunning scene involves a second-hand memory, foggy and uncertain, as dreamlike as any drawn in Flee. But the details of this memory remain (intentionally) untranslated, narrated in an indigenous tongue Magdalena doesn’t speak. Absent the symbolic, the abstract finality of language, we can only connect by way of feeling. We receive, instead, precisely what we must.

2. Toxic Defenses: The Power of the Dog and The Killing of Two Lovers

Hurt people hurt people. While there’s truth to the sentiment, it isn’t a particularly helpful diagnosis: Everyone is a “hurt person,” at least to some degree. It’s the mechanism that I find more interesting to probe, both as a tool for understanding and a cautionary tale. There’s an innate response to hurt, an inner hardness we develop, that can fester into outward-facing anger: to dig in our heels amid intractable trauma and transmute it into vitriol, resentment, obsession. We’re currently watching it play out at scale.

Two tightly coiled dramas explored that nefarious redirection: the unpredictable threat of a defense that’s curdled.

Menace clings to every frame in The Power of the Dog. Befitting a Gothic Western set in 1920s Montana, some of that comes with the territory: stampeding animals, tumbleweed rot, death as a daily intrusion. But if the wilderness demands a certain jaggedness from everyone, Phil seems to particularly luxuriate in it. He’s a gaping wound with a dirty rag draped over it. He wants it to fester, and wants you to know it. When his brother’s wife Rose and her son come to live with him, he marks them as “soft” and sets on a mission to break them: caustic looks, half-uttered insults, a nearly invisible tightening of screws. Even if Rose could confide in her husband, what tangible proof could she offer? Phil’s contempt is so strong it needs no physical medium; he plucks at her flaws with virtuosic precision. You’ve seen enough movies (or read enough of that intro) to intuit where all this is going. Yet far from spoiling the experience, that intuition is just another instrument, one the film will play with similarly unnerving expertise. The Power of the Dog aims to make something inside of us curdle, to blur the lines between protection and violence. It compels us to recognize the rot from within.

Menace clings to every frame in The Power of the Dog. Befitting a Gothic Western set in 1920s Montana, some of that comes with the territory: stampeding animals, tumbleweed rot, death as a daily intrusion. But if the wilderness demands a certain jaggedness from everyone, Phil seems to particularly luxuriate in it. He’s a gaping wound with a dirty rag draped over it. He wants it to fester, and wants you to know it. When his brother’s wife Rose and her son come to live with him, he marks them as “soft” and sets on a mission to break them: caustic looks, half-uttered insults, a nearly invisible tightening of screws. Even if Rose could confide in her husband, what tangible proof could she offer? Phil’s contempt is so strong it needs no physical medium; he plucks at her flaws with virtuosic precision. You’ve seen enough movies (or read enough of that intro) to intuit where all this is going. Yet far from spoiling the experience, that intuition is just another instrument, one the film will play with similarly unnerving expertise. The Power of the Dog aims to make something inside of us curdle, to blur the lines between protection and violence. It compels us to recognize the rot from within.

The Power of the Dog reveals its characters’ torment methodically; The Killing of Two Lovers exposes it in the opening scene. We begin with the sound of David breathing, amid some industrial clatter. We then see his face, framed in claustrophobic aspect, before a cut reveals the still-sleeping couple by his side. One of them is Nikki, his wife and mother of his children. The other, as of now, remains a stranger. David’s looking down at them with such a childlike hurt, we feel a pang of pity…that is, until we see the pistol he’s aimed squarely at their heads. He won’t pull the trigger, at least not yet. But that uneasy juxtaposition—the boyish look in close-up, the loaded gun in wide—it permeates the rest of the film. Outwardly David seems like an affable guy, a father coping with separation as well as one might expect. He picks the kids up, on time and excited; he spends hours memorizing Hedberg riffs to quote back to his boys. When his eldest daughter expresses hatred for her mother, he responds with the conviction of a Very Special Episode: marriage is hard, Nikki’s a wonderful woman, everybody’s trying their best. And yet, there was the gun, and the innocent expression as he held it. For long stretches of the film we’re shown nothing of the weapon, but that whiff of boyish charm serves as a proximate threat. We stay lodged in that discrepancy like a bullet in the chamber, waiting for some inevitable release.

The Power of the Dog reveals its characters’ torment methodically; The Killing of Two Lovers exposes it in the opening scene. We begin with the sound of David breathing, amid some industrial clatter. We then see his face, framed in claustrophobic aspect, before a cut reveals the still-sleeping couple by his side. One of them is Nikki, his wife and mother of his children. The other, as of now, remains a stranger. David’s looking down at them with such a childlike hurt, we feel a pang of pity…that is, until we see the pistol he’s aimed squarely at their heads. He won’t pull the trigger, at least not yet. But that uneasy juxtaposition—the boyish look in close-up, the loaded gun in wide—it permeates the rest of the film. Outwardly David seems like an affable guy, a father coping with separation as well as one might expect. He picks the kids up, on time and excited; he spends hours memorizing Hedberg riffs to quote back to his boys. When his eldest daughter expresses hatred for her mother, he responds with the conviction of a Very Special Episode: marriage is hard, Nikki’s a wonderful woman, everybody’s trying their best. And yet, there was the gun, and the innocent expression as he held it. For long stretches of the film we’re shown nothing of the weapon, but that whiff of boyish charm serves as a proximate threat. We stay lodged in that discrepancy like a bullet in the chamber, waiting for some inevitable release.

1. Present-Tense Memories: C’mon C’mon and Pig

Last year’s themes were phrased as lessons, with the final two intended as a couplet: “Find beauty in the motion blur; find meaning in the stillness.” Befitting the all-or-nothing nature of the start of the pandemic, I viewed these as separate directives, a progression of sorts. Grieve the memory of a past-tense togetherness, then find solace in our solitary present.

These films argue that, through quiet intentionally, we can achieve both at once. They insist that to fully be alive is to embrace some continual collision: blur and focus, grief and celebration, blank-slate openness and world-worn wisdom. To cast every present moment in the glow of reminiscence, and to remember past detail with the immediacy of experience.

A man and a boy are walking together through a black-and-white, bustling Manhattan. Johnny is weary and pensive, probably in his late 40’s; his fidgeting nephew Jesse is 9. Jesse’s never been to The City before, and he’s wired on cacophony and sugar: head bobbing, limbs squirming, eyes strained in an effort to see everywhere at once. He’s a human antenna, donning headphones designed for a head twice his size and waving a big, fluffy microphone. Johnny’s patiently suggesting recording techniques, but Jesse’s way too excited to listen. They’ll capture it together, somehow. C’mon C’mon is a movie that documents life as we live it, and I realize that makes it sound cheesy. That’s okay. Whether you’re a jittery nine-year-old brimming with questions or an adult too exhausted for answers, a great deal of your life is certain to be cheesy—and forgotten. How many late night epiphanies can you still recall? What’s the half life of a fit of unexplained laughter—the kind that hit without warning and slowly devolved into dumb, incommunicable tears? Their mic is storing this to tape, but would it matter if it weren’t? It’s the intention to preserve that renders the feeling immortal. “I’ll remind you of everything.”

A man and a boy are walking together through a black-and-white, bustling Manhattan. Johnny is weary and pensive, probably in his late 40’s; his fidgeting nephew Jesse is 9. Jesse’s never been to The City before, and he’s wired on cacophony and sugar: head bobbing, limbs squirming, eyes strained in an effort to see everywhere at once. He’s a human antenna, donning headphones designed for a head twice his size and waving a big, fluffy microphone. Johnny’s patiently suggesting recording techniques, but Jesse’s way too excited to listen. They’ll capture it together, somehow. C’mon C’mon is a movie that documents life as we live it, and I realize that makes it sound cheesy. That’s okay. Whether you’re a jittery nine-year-old brimming with questions or an adult too exhausted for answers, a great deal of your life is certain to be cheesy—and forgotten. How many late night epiphanies can you still recall? What’s the half life of a fit of unexplained laughter—the kind that hit without warning and slowly devolved into dumb, incommunicable tears? Their mic is storing this to tape, but would it matter if it weren’t? It’s the intention to preserve that renders the feeling immortal. “I’ll remind you of everything.”

That line could easily have been uttered by Robin, the monklike protagonist of Pig. Having emerged from the forest after years of self-imposed seclusion, the chef functions as a conscious well of memory. It isn’t just that he remembers on behalf of other people (though he recalls every meal he’s cooked and every patron whom he’s served). It’s that his very demeanor—unflinching directness, uncanny attunement, ability to coax out the senses in others—it acts as a catalyst. Robin encourages; he conjures; he makes space for remembrance. A mystical meditation on the power of presence, Pig tells us that to fully experience a moment is to commune with its history. Every sense memory is a security deposit box, an underground truffle, a bottled vintage nestled under layers of dust: tiny, hidden Horcruxes, fragments of ourselves, containers of a prior present waiting to be uncorked. The best meal of your life. A film that makes you cry. A now-empty restaurant whose clattering once covered a thousand whispered intimacies. By staying open to the immediate, we become historians and time travelers: present in memory, transparent in hurt, connected to others, clarified to ourselves, unburdened, unwavering, unexpectant, unguarded, unhurried, relaxed, resilient, and found.

That line could easily have been uttered by Robin, the monklike protagonist of Pig. Having emerged from the forest after years of self-imposed seclusion, the chef functions as a conscious well of memory. It isn’t just that he remembers on behalf of other people (though he recalls every meal he’s cooked and every patron whom he’s served). It’s that his very demeanor—unflinching directness, uncanny attunement, ability to coax out the senses in others—it acts as a catalyst. Robin encourages; he conjures; he makes space for remembrance. A mystical meditation on the power of presence, Pig tells us that to fully experience a moment is to commune with its history. Every sense memory is a security deposit box, an underground truffle, a bottled vintage nestled under layers of dust: tiny, hidden Horcruxes, fragments of ourselves, containers of a prior present waiting to be uncorked. The best meal of your life. A film that makes you cry. A now-empty restaurant whose clattering once covered a thousand whispered intimacies. By staying open to the immediate, we become historians and time travelers: present in memory, transparent in hurt, connected to others, clarified to ourselves, unburdened, unwavering, unexpectant, unguarded, unhurried, relaxed, resilient, and found.

Closing Bits, Shameless Plugs

Hi there! If you made it this far, there’s a good chance you’ll enjoy some of my other writing. You can dig through previous years’ write-ups, or find a bunch of individual film reviews. On a personal note, I undertook a hundred days of journaling towards the beginning of the pandemic. You can find that and other miscellaneous writings scattered throughout this site.

Given the still-mostly-virtual year, almost every film I listed is available to watch at home today. Linking to each felt like a nightmare for future readers, as these are certain to change month to month. But as of January 31, 2022:

- The Power of the Dog, The Lost Daughter, Bo Burnham: Inside, Tick Tick Boom, and Bad Trip are available on Netflix

- Pig, The Killing of Two Lovers, Test Pattern, Bergman Island, and The Humans are available on Hulu

- Judas and the Black Messiah and The Fallout are available on HBO Max

- Slalom is available with an Amazon Prime subscription

- C’mon C’mon, Flee, Identifying Features, Mass, The Card Counter, The Green Knight, Spencer, and Language Lessons are available for rent or purchase on most platforms.

- Only Întregalde, Licorice Pizza, and Compartment No. 6 remain unavailable.

This marks my eighth consecutive year of film recaps, which is solely a labor of love. I am fortunate enough to need no financial support, and would reject any if offered. But there is one form of support I’m willing to grovel for: If you read and enjoyed this, I would love to hear from you! These things always get some level of traffic, but a faceless graph on my Google Analytics dash is a poor substitute for human connection. You can hit me up on Twitter, connect with me on Letterboxd, or just send a friendly email to stephen __at__ cs.stanford.edu.

-

Zola, Titane, The Last Duel, The French Dispatch, Spencer, House of Gucci, C’mon C’mon, Ghostbusters: Afterlife (for reasons unclear even to me), Licorice Pizza (in 70mm, at the height of omicron, solely for the sake of this list).↩

-

Off the top of my head: Red Rocket, West Side Story, Spiderman: No Way Home, Drive My Car, Memoria, Parallel Mothers, Nightmare Alley, The Souvenir Part II↩

-

With the exception of the animated documentary Flee, I restricted this to narrative fiction as a matter of convenience. That alone left a handful of fantastic films on the cutting room floor: most notably Summer Of Soul, but also Homeroom and The Rescue. Some excellent, caveat-free favorites simply felt wrong to pair with others, or were otherwise lost in the shuffle. These include Petite Maman, Saloum, and (most glaringly) Titane. Others reflect the strange nature of hindsight: I fell hard for CODA at its Sundance premiere, but had lost all enthusiasm by New Years. Still others speak to the hazy nature of release schedules and awards qualifications. For instance, The Father and Minari were both 2021 contenders by my selfish criteria (festivals count if I attended, don’t if I didn’t), but they are so tied to the 2020 Conversation™ it felt awkward to include them. Whereas Judas and the Black Messiah, despite being in the same early awards conversation, screened at Sundance 2021 and thus felt natural to include. None of this is rational or fair: Go see them.↩

-

Though I always like to say that pairing isn’t a science, it does involve an awful lot of formulas and a Big Ass Google Spreadsheet. (If you don’t care about process, please bail from this footnote now!) I started with roughly 30 candidates worthy of inclusion, as well as my Spoiler Warning list to keep me honest. I then jotted down potential pairings (about 50 in total), till every candidate had multiple points of entry. With the help of some truly sweaty formulas and conditional formatting rules, I was able to nominate and stack rank certain pairings, getting yelled at if a favorite was neglected or if any film was double-counted. Eventually, I landed on something that felt right. Broadly speaking, the higher the ranking the more I liked (some weighted combination of) the movies, and my favorite of each pair is typically listed first. For comparison, my top 5 on the podcast were C’mon C’mon, Pig, The Power of the Dog, Flee, and Test Pattern. In conclusion: If you squint real hard, it sorta looks like a science?↩

-

For that, I suggest Lauren Hadaway’s The Novice.↩

-

Nothing to see here, Mom!↩

-

The performers’ delight, as well as the thrill of the real-world actors who play them. Which is a surprisingly deceptive layer: The scene feels so kinetic, it’s easy to forget that we’re only watching a reenactment of performance. Every time, it still floods me with the adrenaline, the rooting-for-them energy, of a live high-wire act.↩

-

Those John Michael Higgins scenes completely sucked the oxygen out of the movie: They’re unnecessary, unfunny, and undeniably offensive. That particular controversy I can co-sign.↩